I want to start this post by saying plainly that I believe that it is possible for writers to create important and insightful work about cultures to which they do not belong. There is a somewhat crude (but, it seems to me, increasingly common) form of postcolonial criticism – often proceeding from a partial, or second-hand, understanding of the work of Edward Said – which argues that this is not the case. At its most strongly stated, this position dismisses all use of “exotic” (usually third world) cultures and locations by “privileged” (usually first world) authors as straightforward cultural appropriation, simply reproducing and reinforcing power dynamics that were set in place by European imperialism. This can lead to the belief that the “right” to write about specific cultures, particularly marginalised or oppressed communities, belongs only to those from within that culture[ref]The definition of culture here is, for me, complicated. What “culture” is mine? How is my “ownership” of a culture proscribed by geographical, ethnic, social or temporal boundaries and how do I prove my “rights” to that culture? How far, for example, does my “Irishness” give me the right to write about those who have radically different histories within Ireland? There are obvious potential limits to my experiences – I can only speculate about the different perspectives that are afforded with different genders or ethnicities. In the deeply divided culture of Northern Ireland, how valid are my speculations about a Protestant (I’m Catholic) character even if we share many characteristics? And cultures are rapidly evolving things – I would similarly be speculating, for example, if I tried to write about someone whose character was formed in generations outside my own. The Northern Ireland I grew up in was radically different from the one my parents’ generation knew and it has changed even further for those who grow up in Northern Ireland today. I know the history but it is not my experience. I can get angry or upset when I read about what was done in the past but these sympathetic emotions are not the same as those that surface when I recall what happened to me and my friends. I am sceptical, therefore, about those who claim that they possess some unique signifiers that allows them to speak authoritatively for large groups of people who they describe as belonging to “their” culture.[/ref].

I want to start this post by saying plainly that I believe that it is possible for writers to create important and insightful work about cultures to which they do not belong. There is a somewhat crude (but, it seems to me, increasingly common) form of postcolonial criticism – often proceeding from a partial, or second-hand, understanding of the work of Edward Said – which argues that this is not the case. At its most strongly stated, this position dismisses all use of “exotic” (usually third world) cultures and locations by “privileged” (usually first world) authors as straightforward cultural appropriation, simply reproducing and reinforcing power dynamics that were set in place by European imperialism. This can lead to the belief that the “right” to write about specific cultures, particularly marginalised or oppressed communities, belongs only to those from within that culture[ref]The definition of culture here is, for me, complicated. What “culture” is mine? How is my “ownership” of a culture proscribed by geographical, ethnic, social or temporal boundaries and how do I prove my “rights” to that culture? How far, for example, does my “Irishness” give me the right to write about those who have radically different histories within Ireland? There are obvious potential limits to my experiences – I can only speculate about the different perspectives that are afforded with different genders or ethnicities. In the deeply divided culture of Northern Ireland, how valid are my speculations about a Protestant (I’m Catholic) character even if we share many characteristics? And cultures are rapidly evolving things – I would similarly be speculating, for example, if I tried to write about someone whose character was formed in generations outside my own. The Northern Ireland I grew up in was radically different from the one my parents’ generation knew and it has changed even further for those who grow up in Northern Ireland today. I know the history but it is not my experience. I can get angry or upset when I read about what was done in the past but these sympathetic emotions are not the same as those that surface when I recall what happened to me and my friends. I am sceptical, therefore, about those who claim that they possess some unique signifiers that allows them to speak authoritatively for large groups of people who they describe as belonging to “their” culture.[/ref].

In disagreeing with the crudest form of this argument I don’t want to deny Said’s basic point: culture played and continues to play a key role in reinforcing the position of the powerful in relation to those they seek to dominate. Nor would I want to underplay the threat posed to marginalised groups by cultural appropriation. But, like Said, I believe that there are dangers in oversimplifying this issue.

In Culture and Imperialism (C&I), Said reflects upon the debates started by his most famous work, Orientalism (O). He uses this opportunity to forcefully reject the lessons that some readers had taken from Orientalism – in particular that artists should be exclusively concerned with the parochial or that cultures should be fenced in for the exclusive use of just one group. “I have no patience with the position that ‘we’ should only or mainly be concerned with what is ‘ours’ any more than I can condone reactions to such a view that requires Arabs to read Arab books, use Arab methods, and the like” (C&I xxviii). Nor was Said simply dismissive of those works that carried the taint of cultural appropriation. Even when he explains how works like Kipling’s Kim or Conrad’s Nostromo carry within them the assumptions and power relations of Western hegemony, Said continues to regard them as “estimable and admirable works of art and learning, in which I and many other readers take pleasure and from which we derive profit” (C&I xv). The temptation to dismiss any attempt to reach across cultural boundaries in literature leads towards an isolationism that Said explicitly rejects: “the narratives of emancipation and enlightenment in their strongest form were also narratives of integration not separation” (C&I xxx – Said’s emphasis).

It is also important to avoid the nativist fallacy. Taking as an example the increasingly metaphysical later writings of WB Yeats, Said argues against the idea that the native possesses some essential qualities that mark them as the bearers of special insight, of being in mystical commune with nature and the “truth” of their land. Nativism is a trap – far from providing escape from imperial rule it has, too often, simply reconstituted divisions along the lines of narrowly defined differences created under imperialism. Thus nativism has reinforced “pathologies of power” that block genuine progress towards liberation. There are powerful reasons for seeking to get beyond these “nativist identities” and:

…not remaining trapped in the emotional self-indulgence of celebrating one’s own identity. There is first of all the possibility of discovering a world not constructed out of warring essences. Second, there is the possibility of universalism that is not limited or coercive, which believing that all people have only one single identity is – that all the Irish are only Irish, Indians Indians, Africans Africans, and so on ad nauseum. Third, and most important, moving beyond nativism does not mean abandoning nationality, but it does mean thinking of local identity as not exclusive, and therefore not being anxious to confine oneself to one’s own sphere, with its ceremonies of belonging, its built-in chauvinism, and its limiting sense of security. (C&I 277)

Said, then, while offering a ways to understand how literature is embedded within and contributes to discourses of power was not advocating the ever finer dicing of art into discrete sections each of which belong only to those possessing the “genuine” right to their expression. When Said came to write an afterword to Orientalism in 1995 (twenty years after its original publication) he said the book was “meant to be a study in critique, not an affirmation of warring and hopelessly antithetical identities” (O 340).

The point of this discursive introduction is to make clear that the criticism I’m about to heap on Stina Leicht’s books is not due to my believing that she, as an American, is intrinsically incapable of writing convincingly or with insight about Northern Ireland or that all such works are inevitably doomed to fail. Like Said, I believe that there is “a profound difference between the will to understand for the purposes for co-existence and humanistic enlargement of horizons and the will to dominate for the purposes of control and external dominion” (O x). Leicht’s intentions are clearly not linked to attempts to dominate, but just because it is possible to write well about cultures outside one’s own does not mean that it is easy. And good intentions are no defence from criticism when an author makes a balls of things.

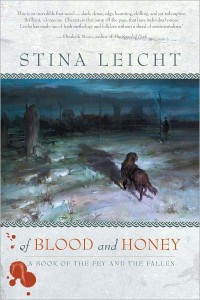

Leicht’s books are “urban fantasy” set in Northern Ireland during the 1970s amidst the early days of “The Troubles”. Their protagonist is Liam Kelly, a young Catholic from Derry to whom a great deal of shit happens. Of Blood and Honey covers the period from 1971 to 1977 – in that time Liam (amongst other things) gets interned in the Long Kesh, gets raped, discovers that he is a shapechanger, joins the IRA, gets imprisoned (again), learns to drive, discovers he’s the best driver ever, drives the getaway car in IRA bank robberies, kills an RUC officer, gets married, discovers that his long absent father is actually a member of an ancient Irish race of “fey” warriors[ref]Leicht’s representation of Liam matches, rather unfortunately, many of the points made at the end of this post by Aliette de Bodard where she sets out how fantasy often makes a terrible hash of the representation of people from “mixed-race” backgrounds. Liam has both the mental health problems and the neatly defined cultural characteristics that de Bodard identifies as both typical of fantasy’s portrayal of people of mixed-race and as deeply problematic. Indeed Leicht states that mental health problems and a tendency to commit suicides are fundamental to people like Liam.[/ref], discovers that there are demons (fallen angels) on Earth, discovers that his local priest is a demon hunter, discovers that his pregnant wife has been raped, murdered and mutilated, discovers that his wife and the priest had connived in the abortion of an earlier child and a whole heap of other stuff. It’s hectic, and it all happens in less than 300 pages that are made even more breathless by the fact that Leicht’s protagonist is often on the edge of hysterics. The second book, And Blue Skies from Pain, covers a shorter period, about a year following almost directly from the end of the first novel, and moves at a slightly slower pace over a slightly longer page count – it encompasses Liam’s confinement by Milites Dei, an order of demon hunting priests, a battle with the ghost of a dead policeman, Liam’s pursuit and capture by his former colleagues in the IRA, his struggle to come to terms with his “true nature” and a showdown with demons.

My problems with the Fey and The Fallen books (as the series refers to itself) start with some minor issues of detail that reveal Leicht’s lack of insight into the setting of her story, but they quickly developed into more serious issues with her portrayal of the politics and people of Northern Ireland.

Let me start with the more minor stuff.

Leicht’s writing is scattered with distracting Americanisms, autumn becomes fall, someone drives a block in Belfast and cars skid on pavement and people walk on sidewalks (what the Americans call pavement we’d call tarmac, and we call pavement they call sidewalk OBAH 134). And it isn’t just the choice of words, there are moments when she transplants American habits across the Atlantic to jarring effect. There is, for example, a long scene where a group of working class Irish men are sitting around having coffee and donuts for breakfast. Try as I might, I couldn’t imagine my dad and the men he worked with sitting down to coffee and donuts for breakfast – if it wasn’t fried in lard, they didn’t eat it [ref]Actually breakfasts bothered me throughout both books – they’re a bit of a recurring theme and yet The Ulster Fry is (as far as I can remember) completely absent. Writing about life in 1970s Nor’n Ir’n and not mentioning soda bread, potato bread, a bit of sausage, bacon and a good fried egg seems perverse. When things were bad The Ulster Fry was often the only thing that was worth getting out of bed for. It is also our single great contribution to the world of cuisine.[/ref]. Leicht replaces the word donut with the local idiom “gravy ring” (ABSFP chpts 22&23) but that only serves to make the whole sequence seem even more anachronistic. Then there’s the moment when Liam’s wife complains that she can’t visit the doctor because “We don’t have enough money” (OBAH 87) – which given that Northern Ireland is served by the National Health Service (the greatest of British institutions – credit where it’s due) and free at the point of delivery, is just wrong. Someone talks about a father doing well enough to put two kids through university (ABSFP 152), but in Northern Ireland this was the era of full student grants (another British scheme) and the barriers to people going to university were primarily cultural and not financial. And there’s someone suggesting that they should play the card game “Go Fish” (ABSFP 262) – an American game that I had to look up on Wikipedia to find out what Leicht was talking about. These are all things that would seem perfectly normal in an American setting but, I think, must feel gratingly wrong to anyone who actually knows Northern Ireland.

Many of these problems could probably have been avoided by some judicious and informed editing and no doubt most of the audience, those not familiar with Northern Ireland, won’t even notice that these things are out of place, but they are indicative of a wider failure with Leicht’s writing. She just doesn’t understand the place and people she’s writing about.

Leicht has no ear for how the Northern Irish speak and her dialogue, even when it isn’t horribly packed with infodumping[ref]This is one of my favourites: “Queen Mary’s father was King Henry the Eighth. The one who established the Church of England. The Pope excommunicated him for divorcing Mary’s mother. Henry killed English Catholics who wouldn’t convert. Mary didn’t agree with her father. So it was when Mary eventually became Queen long after her father’s death she abolished the Church of England. Burned three hundred Protestants for heretics, Father Murray said. It was then that the hatred between Catholics and Protestants was born.” (OBAH 56) How’s that for a history of the reformation in England in 77 words!? It isn’t just that this is a ludicrously simplistic version of history (though it is) or even that it’s a horrible piece of dialogue (who, except maybe a university lecturer or a museum guide in a hurry, would talk like that?) but, worst of all, it isn’t relevant to anything that actually happens in the novel. And there’s tonnes of this stuff littering both books.[/ref], can clang dreadfully. There are problems with word choices[ref]Like the frequent use of the word “mate” in ABSFP, a usage which strikes me as a peculiarly English. It certainly isn’t a word I used until I moved to England, I think. Another example is the way people in the books refer to the British Army as the BA… every time I read this I thought of a large black man with too much jewellery and an aversion to flying in planes. This bothered me (not the image of Mr Baracus) because Leicht uses the acronym with such confidence that I assume she’s got it from some book she’s read, but I asked friends and I searched the Internet and I couldn’t find anyone who referred to “the Brits” as the BA, indeed everyone I mentioned it to just laughed and mentioned the A-Team. And yet, Leicht is so confident…[/ref] but her writing is at its worst when she slips into an attempt to approximate the Northern Irish accent and delivers a Yoda-ish jumble that might have come from an old John Wayne movie (to be sure, to be sure) and can’t be read with a straight face.

“It’s the man of the house, you are. And I’ll not shame you.” (OBAH 53)

“Suffered you have. Made great sacrifices for the cause.” (ABSFP 136)

Transcribing idiomatic speech with strong accents is a tricky job, so, for the most part, Leicht’s decision to avoid this difficult task is understandable (especially since she’s so bad at it) but it comes with a price. Accents are important in Northern Ireland – they’re one of the key ways people identify where they stand in relation to one and other, which is crucial when a misplaced word could have serious consequences. But, in these books, everyone speaks the same whether they are from Dublin[ref]At one point Leicht has a Dubliner react to a moment of crisis like this: “Bobby’s English was long gone as well as his proper Irish, and he rattled off a long series of swear words in Gaelige

Transcribing idiomatic speech with strong accents is a tricky job, so, for the most part, Leicht’s decision to avoid this difficult task is understandable (especially since she’s so bad at it) but it comes with a price. Accents are important in Northern Ireland – they’re one of the key ways people identify where they stand in relation to one and other, which is crucial when a misplaced word could have serious consequences. But, in these books, everyone speaks the same whether they are from Dublin[ref]At one point Leicht has a Dubliner react to a moment of crisis like this: “Bobby’s English was long gone as well as his proper Irish, and he rattled off a long series of swear words in Gaelige Gealige Gaeilge” (OBAH 155). I think this is a revealing moment in its wrongness. Bobby is a Dubliner – at least we’re told he is the brother of Oran, who is definitely from Dublin – and the number of native Irish speakers born in fifties Dublin must be pretty bloody small. Yet, in this crisis, “the native” emerges as though deep inside all true Irishmen rests the spirit of the hidden Gael only waiting to burst forth. It’s nonsense.[/ref] or Cork or Derry or Belfast. To an outsider, it might seem entirely plausible that Leicht has her protagonist Liam change his name to Billy and seek to escape his past by moving in with Protestants in Ballymena. The two towns are less than 50 miles apart, you can drive from one to the other in about an hour. But, ignoring, for the moment, the fact that the differences between people from the two communities in Northern Ireland are not stripped away simply by changing your name, Liam’s accent would have marked him out as someone from predominantly Catholic Derry, which would have immediately aroused suspicion in predominantly Protestant Ballymena[ref] The people of Ballymena (God bless them) are burdened with an accent that makes the rest of Ireland wince – it’s amongst the most distinctive (and annoying) on the island. Listen to these brave fellas from Ballymena http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3h54t7JrMQ and then this girl, from Derry: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-16686119. To someone from the North these accents don’t just immediately identify where you are from but begin to narrow down your class, your religion and more-or-less everything you need to know about what it is safe to talk about.[/ref] and, suspicions aroused, dozens of other things would have allowed the people he met to see through his lies[ref]There’s an interesting passage early in And Blue Skies From Pain where Liam meets some strangers, border smugglers, and tries to work out what religion they are. Leicht gets close to the way people in Northern Ireland sought to sound each other out, to identify religion and, therefore, their relationship to each other. But the good work in the passage is rather ruined when, for no logical reason (other than to inject an element of drama into the scene, presumably), Liam decides to blurt out his “true identity”. There’s a cheery little song written by Colum Sands that goes “whatever you say, say nothing when you talk about you know what, for you know if you know who should hear you, you know what you’ll get” that neatly encapsulates the more-than-a-little-paranoiac way Northern Irish people approach talking to strangers. Leicht’s Liam wouldn’t have made it to adulthood if he’d actually gone around blabbering like that.[/ref].

The problems don’t stop with Leicht’s use of language. The novels also lack any sense of place. Derry and Belfast, where most of the action takes place, are barely described and feel interchangeable but they’re two cities with very different characters. Lots of Derry is built on hilly ground and with the medieval walls looking over the Bogside and encircling the city centre and the hilly surrounding countryside it has always felt, to me, like a place that’s crowded and looking in on itself. Belfast is a flatter, more open city with, in places, a battered Victorian grandeur. At the same time, with the Black Mountain looming over it, Belfast has always struck me as a gloomier place. Leicht has nothing to say about how these places look and feel because it is obvious that she doesn’t know them and has made no real effort to understand them. The result is a pair of novels in which characters appear to move around against blank canvases, street names appear occasionally but there’s no sense of a solid place behind them.

So there are problems of detail in Leicht’s writing, but the real difficulties for me were in the way she portrays the people and politics of Northern Ireland, specifically the way in which she (fails) to represent the Protestant/loyalist community, her representation of the British and her portrayal of nationalism. I’ll deal with these in turn.

The representation of loyalists

At the start of The Troubles some two thirds of the population of Northern Ireland did not identify themselves as Catholic. You’d be hard pressed to tell that from Leicht’s books. There’s the occasional reference to Liam’s Protestant uncle, there are some policemen (members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary – RUC) who get to rush around shouting “Taig” and “Fenian”, there’s a gang of inexplicably murderous Protestant smugglers who appear briefly at the start of the second book and there’s a Protestant punk[ref]It is possible that, despite all the other stuff I’m talking about here, the thing that annoys me most about Leicht’s book is the way she takes punk culture, which at its inception in Northern Ireland was resolutely working class and occupied the hollowed out heart of Belfast when almost no one else went there at night, and turns it into a horrendous frat party with University students lolling about in some rich fops large suburban house. And they all talk like hippies. Bah![/ref] who hosts a party Liam attends and says, I think, one sentence. And that, as far as I recall, is it.

It’s not an impressive showing and it is problematic because by excluding this part of the population of Ireland from her novels, Leicht is (consciously or otherwise) saying something about their status. The Catholics have their “fey” – the true spirits of Ireland – who are plugging away on their behalf, they have the church[ref]Apparently Protestant clergy don’t fight demons, only Catholics. It’s a shame, because Reverend Ian Paisley: Demon Slayer is surely a better and more exciting idea for a movie than Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.[/ref] with its cool kung fu nuns and kick-ass priests, they have their mystical native powers and they have their injustices shown and their “cause” constantly justified. They have a monopoly on suffering and their pain is given a face and we are given reason to empathise with them. The Protestants get none of this. So, in Leicht’s book, even when she is protesting that the violence is terrible and everyone is just the same, Protestants are absent. And what, it seems to me, Leicht is saying (consciously or otherwise) about the status of Protestants by excluding them from any serious focus in her book is that they do not really belong in the Ireland she is creating. The peace process, for all its flaws, is built on the understanding that Northern Ireland’s future hopes of peace, security and prosperity rest on the two communities recognising that neither has an exclusive claim to the history, the culture and the future of the Province. It’s a shame none of this understanding makes it into Leicht’s books.

Now I grew up a Catholic on a Housing Executive[ref]The British governments couldn’t trust the gerrymandered councils to treat housing fairly, so Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK that didn’t have council housing estates.[/ref] estate in Northern Ireland and my sympathies are instinctively nationalist. As such Leicht might expect someone like me to be broadly supportive of the way she portrays Northern Ireland, it plays to some pretty deeply founded prejudices that I grew up accepting without question. But, in fact, I found the absence of any genuine empathy for the other side of the community deeply uncomfortable. I expect actual Ulster Protestants reading these books – especially those who have lost friends and family – would, justifiably, be enraged. Perhaps the most insensitive and disturbing example of Leicht’s treatment of Protestants is the way she absolves her hero of the murder of a RUC officer. Liam’s wife, Mary Kate, tells him:

I know. About the constable. It’s all over the papers. The radio. The telly. I don’t care. Sooner or later it was going to come to killing… You only did what you had to do. That constable had to have known. He’d have felt the same, were it you and not him. (OBAH 144)

And then, for several pages, Liam gives his confession to a priest (an IRA “chaplain”) who is only too keen to grant absolution:

According to the Church, there is such a thing as a justified war… In order for there to be peace, sometimes someone must make a stand for those who can’t stand for themselves. Negotiation is the first moral option, of course. So, we attempt time and again. But the British are never serious about negotiations. They’ve demonstrated that. It’s on their heads. (OBAH 149)

I wouldn’t deny that there were people in Northern Ireland who justified the actions of IRA volunteers in these terms and who would remain sympathetic to this viewpoint even today. However, I believe, there is something deeply problematic in their use in this work of fiction. This is the only perspective we have on the meaning of this act of violence. The policeman is just an empty space. Mary Kate may encourage Liam to put aside his worries because killing was bound to happen “sooner or later” but the death of the RUC officer is treated differently from the deaths of Catholics in the book. The death of Mary Kate and, later, Liam’s friend Oran, have repercussions throughout the two volumes – they literally haunt Liam. And yet, once absolved of his sins, Liam never returns to the death of the RUC officer in the same way.

It is not my purpose here to defend or justify what the RUC sometimes did[ref]The RUC and the UDR both did horrible things – as the Stevens Inquiries uncovered – rather than keeping the peace and enforcing the law in a fair and balanced way, they frequently acted as adjuncts to the Loyalist terrorist groups. Indeed, often enough, they were the Loyalist paramilitaries.[/ref] and I had enough personal experience of them to know that they could be right bastards. But my concern is the fact that there are no consequences to this death – or any human face given to the suffering of the entire Protestant community anywhere in Leicht’s books – and this results in a portrait of Northern Ireland that is dangerously skewed. I understand why Leicht seeks to wash away the sins of her protagonist, she needs her character to be the hero of her story. That, however, doesn’t change the fact that the result of her selective presentation of history and the absence in her story of an alternative viewpoint means that her Northern Ireland is as one-dimensional, sentimental and misleading as a Republican rebel song.

The Representation of the British

Leicht doesn’t convincingly convey the operations of British military forces in Northern Ireland. There are lots of specific details she gets wrong[ref]My favourite is the moment when she has a character ask a soldier: “Aren’t our papers are in order?” (OBAH 130). This sounds good, it sounds like the sort of thing people say in movies all the time, but it is also nonsense. There were no identity papers in Northern Ireland. He might have handed his driving licence over to the police if he were stopped when driving a car, but there were no “papers”. There are other details, like small groups of police or soldiers (even individuals) wandering aroud Catholic areas without support or describing soldiers as moving in “clusters”, that are minor mistakes that reveal a lack of familiarity with her subject matter.[/ref] but these are, again, incidental to the bigger problem of the way they she represents this group of people.

My experience of the British Army in Northern Ireland was mixed. You sometimes met soldiers who did their job with as much decency as the circumstances allowed, but then again there were also those who did terrible things and then there were some who were just arseholes, like the drunken patrol who took great pleasure in taking turns pissing down the leg of my trousers late on Boxing Day in 1986. In that there were good and bad amongst them they were pretty much like any group of young men set loose in a foreign land, except, instead of lager and an insufficient supply of sunscreen, they came with helicopters, armoured cars and big guns. With Leicht’s books, however, there is no light and shade and there is no realistic representation of the experiences of the British soldier on Northern Irish streets. For the most part the British security services are simply monsters – often literally demonic.

There’s the cruel prison governor who takes sadistic pleasure in raping Liam (OBAH 19-20), there are demon British soldiers who provide cannon fodder for the big shootout (ABSFP 315), there’s the demon Redcap – who takes the form of a paratrooper (they wear red berets, geddit?) in Derry during Bloody Sunday and who rapes and slaughters Liam’s wife and rips their unborn child from her belly, and then there’s Detective Inspector Haddock – who Leicht calls an MI5 officer (OBAH 239 – I think she probably means Special Branch) – who is a preposterous caricature of a villain who becomes a malignant spirit haunting and attempting to murder Liam.

This dehumanisation of the British in Leicht’s books, like the absence of Protestants, contributes to a one dimensional view of the politics and history of Northern Ireland[ref]Of course there were plenty of awful things done by the British forces – from beatings and torture to mass murder on Bloody Sunday, collusion with Loyalist terrorists and “shoot-to-kill” (the deliberate and cold-blooded assassination of suspects and a perversion of the rule of law). Innocent people died at their hands.[/ref]. Even as a teenager, even while those British soldiers were ruining my suede shoes[ref]It was the 1980s, let us not talk of fashion.[/ref] with their urine (well, perhaps a little later), I was aware that some of them were barely older than I was and that (despite being the ones with the big rifles and machineguns) they were in a frightening position too. Who knows why they were behaving as they did: perhaps they were acting in response to their training by the Army; perhaps they were pissed off that they had to spend Christmas in a shitty barracks in Northern Ireland; perhaps their friends had been killed; or perhaps they were just dickheads. Whatever, they had their motivations and to reduce them to beasts and monsters, as Leicht does, seems a serious distortion and gross simplification.

Representation of Nationalists

The IRA plays a very big role in Leicht’s books. Liam joins the IRA when he is interned in the Long Kesh (apparently every male member of his wife’s family is also a volunteer, though she isn’t – it isn’t clear why because she is plainly sympathetic and plenty of women were volunteers) and most of Liam’s friends and acquaintances are also in “The ‘Ra”. Though Liam comes to regret his membership and attempts to escape from it, there are significant ways in which the “cause” of the IRA is reinforced by the choices Leicht makes. While some members of the IRA are represented as “bad guys” – though I think it is significant that in each case they are acting under the control of others (the evil British policeman Haddock in OBAH and a demi-demon in ABSFP) – there are things that are missing from the book that lead to a skewed picture of nationalism.

The only time that the IRA are shown interacting with the wider Catholic community is (in a scene that must surely rank as one of the most inane examples of a metaphor literally applied in any book I’ve ever read) when Liam and Oran go to mend an old woman’s fence that was knocked down by some other IRA men[ref]There’s also some other nonsense about the IRA not stealing cars from Catholics.[/ref]. This leads me to suspect that Leicht is either being deliberately disingenuous or is ignorant of the price the IRA extracted from the community they claimed to be protecting.

There is nothing in either of the Fey and the Fallen books that reflects the fact that Catholics were murdered and suffered “punishment beatings”[ref]A euphemism that covered many sins, not least the favourite blasting away of the kneecaps to leave people permanently crippled.[/ref] or that people were driven from their homes and forced into exile by their “protectors” who were content to use extreme violence to establish and maintain control over their own community. From the earliest days of The Troubles, the IRA, and other republican groups, appointed themselves judge, jury and, too often, executioner in the Catholic community. People were attacked for falling in love with the wrong person, for taking jobs in the wrong place, for appearing too friendly with the Army and for having been accused (proof wasn’t necessary) of petty crime. The terror that the IRA inflicted on its own community is entirely absent in Leicht’s Northern Ireland[ref]And this vigilantism is not dead – thugs are still shooting and beating and killing and using Republicanism as a cover for their criminality.[/ref]. During The Troubles Republican terrorists killed more people in their own, Catholic, community than the British security forces. For every ten Catholics killed by loyalist paramilitaries, the Republicans killed six. From 1976 to 1990 more Catholics were killed by Republican paramilitaries than Loyalist groups. One in three of all Catholics who died during The Troubles were killed by groups who claimed to be defending them – and most of those were civilians, not other paramilitaries killed in the various feuds. There is not the slightest inkling of any this in The Fey and The Fallen.

Nor is there any mention of the economic costs the IRA imposed on their own community. The IRA didn’t just indulge in the kind of knockabout bank robberies that Leicht describes, they leached off the community, demanding protection money and they’d burn out (or worse) businesses that defied them. They made hard times (Northern Ireland was for many decades the poorest part of the UK) even worse.

Nor does Leicht allow any significant space to other forms of nationalism – the Official IRA (later The Workers’ Party), who pursued a Marxist-inspired, anti-sectarian agenda, get a brief mention but the Social Democratic and Labour Party and its form of more moderate nationalism is almost entirely absent[ref]Bernadette Devlin does get a passing mention.[/ref]. Yet it was the SDLP, not the IRA or Sinn Fein, that formed the most important thread of nationalism in the Civil Rights struggle which forms the backdrop to the early parts of Leicht’s first novel and it remained, by some distance, the most widely supported form of nationalism amongst Catholics throughout The Troubles. The SDLP was only surpassed by Sinn Fein after the peace process became established. Leicht seems to assume that every Catholic automatically accepts the basic principles of “the cause” – for example that they support the struggle for a united Ireland. But research shows that attitudes were always more fragmented, with only just over half of Catholics supporting unification even during The Troubles – and since the peace process support has fallen further. There has even always been a small fraction of Catholics who have been staunchly unionist.

Once again the effect of Leicht’s decisions is to simplify Northern Irish politics and history. This is understandable. She is telling a story to people who aren’t au fait with the history of the province. The problem is that this comes at the cost of seriously distorting the truth. Her image of nationalism is as one-dimensional as her portrayal of Loyalists or the British and all of it combines to create an image of The Troubles that suits her storytelling but does a serious injustice to the suffering experienced by real people on all sides in the community.

The obvious question is: does any of this really matter? After all, these are just fantasy novels. Leicht herself, in this interview, admits that she’s not an expert on Irish history and says: “I am a fantasy writer and as much as I love historical fiction, I never really intended to be an historical fiction writer and I never really intended the story to stay in the politics one hundred per cent like it does in the beginning.” If she wasn’t interested in writing a book that is fundamentally grounded in politics then, I’d have to suggest, she might have made a mistake in choosing Northern Ireland as the setting and The Troubles as the subject of so much her story. Leicht goes on to describe a book as being like a buying a ticket for a Disney theme park ride that lets you experience someone else’s life and be in a different place.[ref]There may be more, I was too busy shouting at the computer from this point to listen further.[/ref] And this, I think, is the core of my problem with The Fey and The Fallen. It’s all just a theme park ride, and Northern Ireland is just scenery employed to enhance the thrills and spills and fun. She doesn’t really have anything serious to say, so why worry if her rollercoaster ride results in a twisted and distorted view of history?

The fact that I’ve just written this lengthy (apologies if you’ve got this far – stay for the footnotes, there’s jokes!) screed probably gives away the fact that I think it does matter that these books are simplistic and ill-informed. This is not dead history – little in Northern Ireland’s past truly is – and Northern Ireland continues to be bedevilled by people who want to offer easy answers to difficult questions. The great struggle is to get people to come to terms with the fact that the things that divide them cannot be wished away, that no one possesses a monopoly on suffering and that both communities have valid claims to respect for their cultures and traditions. We have to live with the reality of our histories, not the fairytales we too often tell ourselves, if we are going to move on. I dislike the way Leicht romanticises one group, excludes another and dehumanises a third and it bothers me that the collective impact of these decisions drives her narrative towards the dangerous simplicity of “good versus evil” – the monsters are all on one side, after all, and the good guys are all on the other. And it is worse when she drifts into the kind of naive nativism that no one[edit: no “right-thinking” person] would accept if she were an outsider writing about, for example, Native American or Black African cultures.

The Americans have a long history of romanticising the Irish in the crudest of fashions. Leicht avoids the worst extremes, this isn’t a book that indulges in the simplistic Republicanism of those who sing rebel songs, witter on about “the ould country” and fill the buckets with cash “for the cause”. Her heart, I’m sure, is in the right place and she hasn’t set out to write a book that is offensive. Nevertheless, her lack of understanding, her playing with the politics and her clumsy characterisation combine to create a pair of books that are deeply unsatisfying and thoroughly problematic.

34 responses to “REVIEW: STINA LEICHT’S THE FEY AND THE FALLEN (OR “POOR OULD IRELAND, AGAIN”)”

“there’s the demon Redcap – who takes the form of a paratrooper (they wear red berets, geddit?)”

Er, no. The Paras wear maroon berets. The Royal Military Police wear red berets.

Well, my Collins dictionary defines maroon as “a dark red to purplish-red colour” – so I’m saying that still counts. And I’m pretty sure that’s what Leicht is aiming for.

Except the RMP are nicknamed the “Redcaps”. And I’m not sure the Paras would like to be confused with them. It’s more piss-poor research, not artistic licence.

But it is the Royal Military Police who are actually nicknamed the Redcaps so, as with the MI5 officer/Special Branch mistake, it seems like an example where Leicht is close but not close enough.

Wonderful review, Martin.

Okay, I concede. I wasn’t expecting to be told to be more harsh…

Excellent review, Martin – a fascinating read even though I haven’t experienced the books.

Thank you.

Leicht goes on to describe a book as being like a buying a ticket for a Disney theme park ride that lets you experience someone else’s life and be in a different place.[xx]

Have you recovered your voice yet? That is seriously appalling, though sadly, it not as surprising as it should be. I guess, y’know, Ireland’s cool now, and we’re (mostly) not people of colour, so it’s not at all appropriative to treat Irish history like a theme park, right?

The coffee and doughnuts is hilariously stupid, and no mention of your version of the full Irish quite telling. And while I’m in Dublin I have certainly never heard BA for the British Army either. I do admire your stamina in giving this – uh, work – such a thorough analysis and review!

WRT vi, I think you’re totally right about the way his cursing in Irish is expressed being indicative of the general wrongness, but in all fairness, there were/are a small but significant number of people in Dublin who would speak Irish at home. There were a few in my school back in the day, and I could just about imagine their retaining some curse words, even if they’d lost their Irish. But the combination of ‘in’ and ‘Gaelige’ is stupid (even without the misspelling). It would be either ‘as Gaeilge’ or ‘in Irish’. As you say, the way that sentence is written makes it damn clear it’s all about the inner Gael rubbish, rather than any attempt at accurate representation of real people.

Hallie, glad you enjoyed the review. I should confess that the typo was mine (Gealige/Gaeilge) – teach me to type things in the middle of the night – I’ve corrected it. I’m sure there were people in Dublin who grew up in households that spoke Irish at home – I knew a few myself growing up, though they were mostly from the country – but, as you say, it is stretching it to imagine that those people would be “native” speakers who lapsed into Irish when swearing in a crisis. Also, my Irish is crappy, but as far as it goes it seems to me that the language lacks the bluntness of Anglo-Saxon English and, therefore, is inferior as a medium for swearing. “Fuck” is the national swear-word of Ireland – and if it’s good enough for the gaeltacht…

Totally agree re ‘fuck’ being *the* curse word of choice. The preference for English cursing in Irish speakers is an interesting linguistic observation too. (In case tone isn’t coming through, this is totally sincere!)

I was in Northern Ireland at the time the first of these novels seems to be set (1971-74), and what she is describing is not what I remember. The British Army was always the army or the Brits, never the BA. (And as an Englishman in Ireland at the time, I was as antagonistic towards the army as everyone around me.) And religion was the first and most important thing about any relationship. As a student I was lodging with six other students, and I knew that five were Catholic and one was Protestant before I knew any of their names. I was an atheist, but I lost track of the number of times I was asked whether I was a Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist, and it wasn’t always a joke. Nor were the bombs that went off in Coleraine in middle of one of my final exams. Whatever else, they left a tension in the air that you could never ignore.

Oh, and what you say about accents is spot on. Over three years I found my own Lancashire vowels being flattened by exposure to the Northern Ireland voice. And Ballymena has the sort of accent that you can never mistake for anywhere else.

[…] an excellent review of Stina Leicht’s Of Blood and Honey on Martin McGrath’s blog here. Of Blood and Honey is an urban fantasy set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and it’s […]

I’m one of the clueless Americans who enjoyed the first book immensely, in part because I grew up with the ‘Catholics good, Protestants bad’ view of the Northern Ireland situation, and in part because I too tend towards Celtic romanticism, and mostly because I don’t know any better. What I particularly appreciated was the characterization. Liam felt especially real to me, particularly in that I read his ‘mental illlness’ as him being a young man suffering from PTSD with almost no tools to help him deal with it. (Although I have to admit that I stalled out on the second book.)

I’d also like to contrast Martin’s quotes from Stina’s interview that mention Disneyland with the podcast I recorded with her and Teresa Frohock. In that one she talks at some length about her concern with appropriation, her attempts to get her research right (including reaching out to folks from North Ireland–obviously they didn’t catch all the howlers Martin did), the fact that she tried to write this story several other ways, and the fact that she couldn’t afford to travel to Ireland. I came away with a picture of an author trying very hard to tell the story with respect, knowing that it would likely be flawed. Link: http://www.locusmag.com/Roundtable/2012/03/teresa-frohock-and-stina-leicht-in-conversation/

This isn’t to invalidate Martin criticisms, which I’m sure are valid, but just so that people don’t think those two quotes define Leicht as an author.

Actually my biggest complaint with the book is one Martin *doesn’t* address, [SPOILER] which is that 2/3 of the way through book 1, Mary Kate, otherwise a vibrant character and good counter balance to Liam, becomes a classic ‘woman in the refrigerator,’ and the rest of the story becomes a classic superhero origin story. I found that disappointing compared to how fresh (in terms of structure) the first 2/3s of story felt (to me). But again, I’m in the place of the ignorant and naive reader who doesn’t know enough to spot all the worldbuilding errors.

Karen: I am sure (and I hope I’ve made it clear in the piece) that Stina Leicht did try to get the facts right. I am also sure that her intentions were honourable. I don’t want this to seem a personal attack on her or even on “clueless Americans” in general. I believe that writers using their imagination to try and place themselves in other cultures, however cack-handed a job they sometimes make of it, is still preferable to an isolationism in which we only ever write about the narrow sliver of culture in which we live. And while I’ve had some fun pointing out some of the errors in these books, they only really bother me (well, except maybe the donuts for breakfast thing!!…) insofar as they contribute to a picture of Northern Ireland that is politically/culturally skewed in a definitive direction and one that, I think, is naive and that never questions assumptions that are actually quite contentious.

I did actually write a section about Mary Kate and the uses of rape (both of Liam and Kate) in the books, but it is a difficult subject treat with sensitivity in brief, it wasn’t directly relevant to the broader points I was trying to make and it wasn’t as if the piece wasn’t long enough…

Martin-

I totally understand where you’re coming from. On a more trivial level, I’ve had cause to rail at science fiction novels that get tech that I’m familiar with wrong, especially radar and comms. Likely, other people wouldn’t notice it. But I figure that if a single error or some weight of errors throws me out of the story, then on some level the story is failing to keep me engaged. Obviously the sensitivity level is different for different people with different backgrounds, so I see where you and I had such immensely different reactions to the book.

BTW, next time you do a post with a bunch of footnotes, could you do a ‘link back’ to the main post? I loves me some footnotes, but I ended up doing a lot of scrolling to find my place each time I read one. 😉

Karen, thanks for pointing out the problem with the footnotes. I hadn’t realised they were borked. Fixed now – though that’s no use to you, obviously. Cheers.

I have to say, I suspected this treatment of the Troubles was likely when I read the following interview with the author and, in particular, this quote which troubled me a lot:

Whichever way I try to unpack that statement, I come up deeply worried by it, and your descriptions of how the opposing sides are presented in the novels suggests that my concerns are not misplaced. (Also, I’m a Mancunian and, as such, more than a little niggled by her arbitrarily deciding to end “the Troubles” in 1994. What was 15 June 1996, chopped liver?)

That sentence is a doozy, isn’t it? It is probably just as well I hadn’t seen that before writing the review…

And yes, the idea that the “The Troubles” ended in 1994 is a neat packaging away of things that ignores not just things like the Manchester Corporation Street or Omagh bombings but also the fact that people are still being beaten and killed and trying to kill others on the streets of Northern Ireland to this day.

The approach to research she describes, including the dread words “The established record had been tampered with. That meant not only gathering all the information I could, it meant having to discern the truth of, as well as the motivations behind, its contents” seems likely to create a mindset where it would be fatally easy to dismiss all accounts of punishment beatings, tarring and featherings, knee-capping, protection rackets and so forth as of the same order as WWI reports of “Hunnish atrocities” in Belgium. “Everyone has an agenda and everyone was motivated to lie and distort” sounds like a reasonable approach to researching the Troubles; “Also, the British deliberately changed the record of events and got away with it” is, at best, fatally incomplete.

AJ: All sides were (and remain) acutely aware of the importance of managing perceptions and of manipulating the facts. It is absolutely true that the British state has done its best to hide the facts about collusion and about criminal behaviour on behalf of its own representatives but, as you note, they weren’t alone in twisting the hiding the truth. The mythologies of nationalist struggle or loyalist isolation are both played carefully to present themselves as, by turns, victims or heroes while ignoring their own culpability.

Scepticism is justified – but using it as an excuse to cherrypick support for a particular ideology is not.

There is a case for the British government’s actions to be the subject to higher standards of scrutiny, they laid claim to the moral justification of representing “law and order” and when their actions did not live up to their public standards – when they plainly weren’t applying the principles of justice evenly to all sides in the community – they betrayed a fundamental trust between citizen and state. But that’s an issue of govermental responsibility and not something that justifies what was done to civilians or, for that matter, soldiers.

The point I was trying to make, and the understanding that I think is missing in Leicht’s books, was that the suffering was shared liberally amongst people on all sides. Like I say in the piece above – the important thing is that we strip away the lies and the stories we all tell ourselves about what happened (and is happening) in Northern Ireland and try and face up to the truth and our collective responsibilities.

Martin: I agree entirely, especially about collective responsibility, hence the use of “incomplete” rather than “incorrect” to describe Leicht’s characterisation of the problems in the historical record – the second quotation was again from her interview, to clarify.

The breakfast one irks me quite a bit, because it’s not as trivial as it seems. There’s a basic level of research –what I call the ‘Tour Guide’ level, which is all the basic stuff about a country that a pocket tour guide will tell you –Lo, I summon the very pretty Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness Ireland and there it is: what to expect for the Irish Breakfast. It’s easy to come by and fundamental and not at all expensive to do and it’s the basics. I haven’t read these (I’ve been invited to) but I get suspicious when the ‘established record has been tampered with’ (it’s all a conspiracy!) argument is trotted out… sounds to me like a theory of the Troubles based on a few old Noraid blow-hards. And I count the end of the armed struggle/conflict as 1998, the Good Friday Agreement –1994 was the ceasefire.

By the way, can I write Ian Paisley: Demon Hunter? (he goes to my gym, incidentally. I’ve seen a lot more of the Rev Doc than anyone should)

If she hadn’t actually mentioned breakfasts she’d have got away with it. It is the way they recur and it builds up over the two books that really drives home the lack of understanding of the importance (and ubiquity) of a fry for breakfast in working class Irish families and that weird gap in the research reveals a deeper lack of understanding about the people she is writing about. The oddest thing about the “donuts for breakfast” thing is the way it spreads out across two chapters and really, really rubs it in your face.

I hadn’t seen that interview before writing this article but the conspiracy theory stuff makes sense and makes me wonder whether I might have gone a bit easy on the books. I’ve taken some time to read some of the (very positive) reviews the two books have had in America since writing the article and it is distressing how skewed and simplistic views of Northern Ireland still are, I kind of assumed most people had wised up and moved on…

I’m not sure where I’d place the end of the armed struggle. Two lads from the estate where I grew up were arrested the other day, apparently with a load pipebombs in their car. Someone needs to tell them “the war is over”.

And please, do write Ian Paisley: Demon Hunter. I’ll settle for points after the gross on the movie rights and a promise that you’ll never show me pictures from the gym… shudder!

Thanks very much for writing about this at such length. When I was reading the book, I was concerned about whether it was accurate, but I had no way to judge.

This being said, I have a couple of sub-cultural nitpicks. The books aren’t “urban fantasy”, with the scare quotes. They’re urban fantasy.

I’m even twitching slightly at ‘the Fey and The Fallen books (as the series refers to itself)’. That’s just the name of the series.

And I’ve sort of been there with the little detail– the donuts– being so annoying. I remember a piece of appropriation of Judaism which was mind-boggling in its presumptuousness, but the thing that annoyed me the most was getting a detail of synagogue architecture wrong.

I haven’t read the books in question, but I think this piece also works well in outlining what is generally wrong with many outside portrayals of Northern Ireland.

One nitpick:

I do feel that exotification/romanticisation of (Northern) Ireland, particularly “the Irish struggle”, is often accepted without question, but I disagree that “no one” would accept those examples. More likely, they’d be deconstructed and criticised in some arenas, but if those criticisms made it to the mainstream, I’d be surprised if a bunch of defensive white people didn’t dive in to explain to everyone else that there was nothing wrong with it. So I’m a bit wary of phrasing that seems to imply that racism got solved already.

However, let me bookend this nitpick by reiterating that I found this a very worthwhile read. Thank you!

You’re right, of course. It wasn’t my intention to suggest that racism of other kinds had ben “solved” – perhaps “that no right-thinking person would accept” would have been a more precise phrasing…

[…] A post that discusses Irish cultural appropriation issues in Stina Leicht’s The Fey and the Fa…, very interesting thoughts on cultural appropriation generally and Northern Ireland particularly (though I wish the reviewer had shared thoughts on the way that Irish folklore was incorporated in the novel as well.) […]

Just been linked to this one and all I can say is, um, wow. It’s alarming, though sadly not surprising, that someone like Leicht would try to write a novel set in Northern Ireland without apparently having more than a trivial understanding of its history. Either she wasn’t aware that the Troubles were far more complex than she depicted them, or worse, she knew and didn’t care, because it got in the way of using them as a backdrop to the simplistic good-vs-evil story she wanted to tell. The sheer arrogance of it is astounding.

What strikes me from your description of the book is that the fantasy elements seem entirely unnecessary. The early years of the Troubles is surely a dramatic enough setting for a novel by itself! It clearly was a result of the same sort of thinking that gave rise to Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter; “Yes, this period was a time of great conflict and epic tragedy, but wouldn’t it be more interesting to modern audiences if we put some supernatural elements in?” But at least no one who lived through the American Civil War is still alive to complain about it. This one is set within living memory and treads casually over wounds which are still sore, which makes it all the worse.

Really enjoyed your analysis in this review. I haven’t read the books (I was linked by a friend, Shaun) and don’t plan on it, but your thoughts made me question the reading I’ve done into NI in the past, which has largely been Loyalist-friendly, or at least somewhat neutral. It’s only been in more academic study through reports that I’ve gleaned some of the Catholic side of the struggle (for example, entrenched and institutional bias in things like local authority housing provision).

Do you have any recommendations for works of fiction which you’ve enjoyed about NI, from either a Prod or Catholic perspective?

[…] Review: Stina Leicht’s The Fey and the Fallen (Or “Poor Ould Ireland, Again”) […]

[…] vote for – if you liked Stina Leicht’s Northern Ireland-themed novel, be sure to read this extremely thorough critique about its stunning lack of cultural […]

[…] for me, although according to Calico Reaction’s review (which in turn references the reviews of Martin McGrath, and Liz Bourke at Strange Horizons), ignorance of the conflict allows you to enjoy the novel at […]

Thank you for this. I’m reading it at the moment, because it was part of the Hugo Voting Package. Or at least I *was* reading it, because I think I’ve given it enough pages to prove itself, and it doesn’t sound as if it gets to be any less pure quill PIRA propaganda. While I’m from the Unionist side, one of the things that annoyed me most was the “la la la, the IRA was wonderful to Catholics, mending anything they were forced to break and never stealing from their own side” attitude. I was thinking about the Disappeared while reading the passages you cited. :-/

It’s frustrating, because there are some interesting ideas and characters in the book. I can see why people with no knowledge of the Northern Ireland situation and a yen for a good-v-evil story lapped it up. But I want to read the book it could and should have been.

[…] or knowledge to comment on the accuracy (a very thorough discussion of this can be found here http://www.mmcgrath.co.uk/?p=2210, but beware series spoilers). I think that the politics of the time were portrayed very […]