One of the most common criticisms I’ve heard levelled against The Science of Sleep is that it is a “slight” film – that in it simplicity, wit and even innocence, somehow Michel Gondry’s new film fails to be serious enough. It isn’t intellectual. It isn’t grown-up.

One of the most common criticisms I’ve heard levelled against The Science of Sleep is that it is a “slight” film – that in it simplicity, wit and even innocence, somehow Michel Gondry’s new film fails to be serious enough. It isn’t intellectual. It isn’t grown-up.

In a sense, I suppose, The Science of Sleep is asking for trouble.

First, it is writer/director Gondry’s first film since the excellent (Charlie Kaufman-penned) Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – a film that may well be the most complex and intelligent fantasy film of the last ten years.

Second, English-speaking audiences tend to approach foreign films in general and French films in particular (actually about half the dialogue is in English and there’s a smattering of Spanish too, but this is a French-funded production with a French director), as intellectual exercises rather than entertainment. Perhaps it is because we believe that, because we have to read bits of text, the films are somehow good for us.

Finally, most viewers will have read the reviews or seen the quotes on the posters that claim that the film has moments of surrealism. And, as we all know, any ism must be intellectual.

But when I say that The Science of Sleep is not an intellectual film I am not being rude, I am encouraging viewers approach this film with an open mind or rather, as the film’s poster tagline has it, an open heart.

Stephan (Bernal) is the film’s central character. He is a bruised, innocent, romantic young man who is clearly shaken by the recent death of his father and has been tricked back from Spain to Paris by his estranged mother. Stephan has difficulty separating reality from his dreams – vivid, candyfloss leaps of imagination which take place in a world of funky gadgets made from scraps, cardboard and egg-boxes. It’s a universe where god was a fan of Blue Peter.

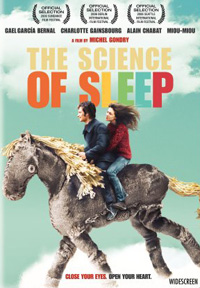

Stephan gradually, slightly reluctantly, becomes infatuated with Stephanie (Gainsbourg), the girl who moves in to the flat across the hall. But, while Stephanie shares his ability to make the fantastic from the mundane, there is an impenetrable barrier between them. Stephan can never entirely escape from the trap of his own imagination and he is always trying just a little too hard. As their courtship struggles to reach any sort of consummation, The Science of Sleep is filled with wonderful imagery and ideas – the one-second-time-machine, a marvellous robotic horse, cellophane oceans and cotton wool clouds.

Those expecting chin-rubbing intellectualism will find themselves disappointed. At its heart and beyond the clever visuals, The Science of Sleep is simply a love story between a troubled boy and a reserved girl. Some of the twists and turns of Stephan and Stephanie’s relationship feel a little forced and the time Stephan spends working in the bickering office of a calendar design firm feels like a diversion that adds little except some questionable slapstick. But, while Gondry’s script offers no deep insights, his film is warm and generous and the fantasy elements though sometimes reflecting Stephan’s troubled nature, are most often uplifting. Stephan is not so much running away from the world as constructing a safer, softer place where he can find solace.

That Stephan’s childish innocence remains engaging and the fact that it never crosses over into the creepy or the sickly sweet is a testimony to the quality of Bernal’s performance. The relationship between Bernal and Gainsbourg works exceptionally well, their fractured and vulnerable performances allied to Gondry’s startling visuals deliver a film that feels emotionally powerful even while it retains a quirky distance. The Science of Sleep even delivers and ending that the optimistic can take as happy, though we may never really know whether we are simply drifting off with Stephan on another journey into the cuddly, secure world he has built following the instructions of some Gallic Valerie Singleton.