Sometimes you watch a film and you can’t help wondering what the director was thinking when they made it. A major movie is a huge collaborative effort and the director is the captain of the ship. Everyone looks to them for a sign that they’re all sailing on the right course, that everything is working and that there are no great big icebergs ahead. The director can’t just look confident when things start going wrong, he has to be confident. He has to be convinced that things are going fine and they’ll all soon be safe in harbour with a decent profit and perhaps a nomination or two from the Academy.

Sometimes you watch a film and you can’t help wondering what the director was thinking when they made it. A major movie is a huge collaborative effort and the director is the captain of the ship. Everyone looks to them for a sign that they’re all sailing on the right course, that everything is working and that there are no great big icebergs ahead. The director can’t just look confident when things start going wrong, he has to be confident. He has to be convinced that things are going fine and they’ll all soon be safe in harbour with a decent profit and perhaps a nomination or two from the Academy.

But, sometimes, underneath it all, their subconscious fears leak out onto the screen. And sometime their subconcsious is absolutely right to be terrified. In writing such moments are sometimes called “a signal from Fred”.

Signal from Fred: The author’s subconscious, alarmed by the poor quality of the work, makes unwitting critical comments: “This doesn’t make sense.” “This is really boring.” “This sounds like a bad movie.”

I don’t believe I had ever seen a more obvious “signal from Fred” as the one planted at the start of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man. How else can one explain starting this film with a shuddering car crash. I wouldn’t suggest you go and see the film but go and stand in the car park next to any cinema in which it is being shown and I’m pretty sure you’ll be able to hear LaBute’s subconscious screaming to be set free from this shattering disaster. It’s actually rather endearing, by the end, that the car crash repeats so often that event the dullest witted member of the audience (and presumably the cast and crew) must get the point.

This film is a disaster.

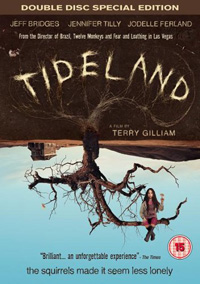

It is very nearly a textbook example of a “signal from Fred”. I say very nearly only because the very next day I saw an even better and more ludicrous example of the same phenomenon. Terry Gilliam’s Tideland ends with a train wreck.

Tideland is a dull, pretentious and ultimately meaningless film which forces the audience to watch Gilliam torture his central character, Jeliza-Rose (Ferland – who is excellent). This eight-year-old girl sees the gruesome deaths of both her drug-addicted parents, including a period where she is left alone in a crumbling and isolated house with her decaying father, before she watches her father’s ex-girlfriend (a taxidermist) extract his entrails and stuff him. Jeliza-Rose then becomes involved with a mentally handicapped young man in a relationship that is riddled with unpleasant sexual tension.

I am not against film-makers taking risks and forcing viewers outside their comfort zone when making films. If there’s a serious point to be made then I’m all for it. And I love much of Gilliam’s earlier work – Brazil, Twelve Monkeys and The Fisher King rank highly on my list of all-time favourite films.

However Tideland has nothing to say – except, perhaps, that “life is shit”.

And if Gilliam’s intention was, simply, to convince the audience of the crappiness of existence then I can think of much better, shorter (at two hours, Tideland is unmercifully long) and more effective ways of doing it than this mixed-up film. Personally I’d rather watch Gilliam scream “life sucks” for two hours than sit through Tideland again. As Jeliza-Rose wanders through the carnage of the train wreck that is the film’s conclusion it is clear that she has suffered for no purpose other than to allow Gilliam to indulge in some macabre imagery.

It is true that the film has visually arresting moments – Gilliam remains a master of images – but that isn’t enough. The pretty pictures can’t hide the emotional vacuum at the heart of this story nor compensate the audience for the rather seedy sensation that they, like Jeliza-Rose, have just been used to gratify some unpleasant urge that has overtaken the director.

Still, no matter how bad Tideland’s train wreck, it is a Sistine Chapel-like work of genius next to the plodding, fright-free bollocks that is Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man. I am not a particular fan of Robin Hardy’s 1973 British original but it is impossible to watch that film and not recognise the effective way it evokes a mood and builds tension or the basic intelligence at work in the dialogue about faith and religion. All of that is missing in this remake. LaBute couldn’t summon up a sense of dread if his life depended on it and the religious aspect of the story has been stripped away – no doubt because much of America’s film-going audience have no stomach for anything that challenges their faith.

The plot sees traffic cop Malus (Cage at his twitching, fidgeting, affected worst) witness a car crash which may, or may not, have killed a young girl and her mother. Damaged by this incident he receives a letter from a long-lost girlfriend who claims that her daughter (and his) has gone missing on the isolated island of Summerisle. Malus goes to investigate, discovering that everyone on the island denies the girl ever existed and that Summerisle is dominated by a strange pagan cult led by women.

If one was being generous one might argue that LaBute has tried to make a film about the relationship between the sexes, but this element of the story is so crudely handled that the film slips perilously close to misogyny. Women are portrayed as wicked old crones or evil seductresses preying on innocent, noble men. In the original Vincent Lee’s Lord Summersisle is given a plausible philosophy with which to challenge his opponent Christian faith. In the remake Burstyn’s Lady Summersisle is played as a stereotypical comic-book villain with her creepy henchwomen terrorising the downtrodden men.

The Wicker Man is a very bad film. Attempts at symbolism – the repeated car crash and a ludicrously overworked bee metaphor – are embarrassingly crude and essentially empty. The acting borders on the inept and the direction and cinematography are flat. The plot is full of silliness that even Scooby Doo writers would be ashamed of (Malus’s tendency to go grave digging/crypt exploring in the dead of night, for example) and stodgy dialogue.

If you’re determined to see one of these (despite what the director’s subconscious and I are trying to tell you) then, for those with stronger stomachs than mine, Gilliam’s Tideland at least offers some reward in terms of the quality of the pictures on screen and a superior cast. The Wicker Man has no redeeming features.