The last time I expressed my disappointment with Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy (Matrix 160) I received a couple of letters that can only be described as hate mail. The unsigned author was keen to point out my mental and genetic deficiencies as well as my ignorance of literature and film. The final paragraph of both letters ended with a question: Given that many millions love them, critics rave about them, awards drip from them and they make huge sums of money, my angry correspondent wrote: “Why should anyone give a fuck what you have to say about The Lord of the Rings?”

The last time I expressed my disappointment with Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy (Matrix 160) I received a couple of letters that can only be described as hate mail. The unsigned author was keen to point out my mental and genetic deficiencies as well as my ignorance of literature and film. The final paragraph of both letters ended with a question: Given that many millions love them, critics rave about them, awards drip from them and they make huge sums of money, my angry correspondent wrote: “Why should anyone give a fuck what you have to say about The Lord of the Rings?”

A fair point, if crudely made.

Nothing I say here will change the fact that The Lord of the Rings trilogy has been the biggest thing to hit cinema screens since George Lucas released Star Wars and these movies will almost certainly have the same sort of long term impact. These have been more than hit movies, more even that hugely successful marketing exercises, they appear to have made a significant mark on the collective consciousness on those who watched them. It is possible, I suppose, that they will imprint themselves on a new generation of fans in the same way that Star Wars did for those who remember the late 1970s and early 1980s.

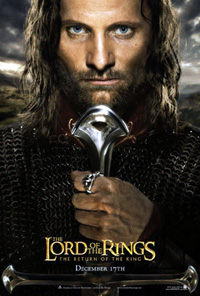

The latest instalment, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, is a technical marvel and a tribute to the determination of cast and crew to create something spectacular. No other film, indeed no other series of films, has come close to matching the richness of the fantasy world built by Peter Jackson and special effects company WETA. They have created beauty and terror, sometimes simultaneously, and deserve the highest praise. They have changed what we imagine is possible on the screen.

Sad that all this dedication, effort and whizz-bangery should have been used in the service of such a hollow, conservative and unfulfilling film.

The Return of the King shares all the faults of its predecessors. It is determinedly “epic” in every aspect of its construction – with pompous dialogue, portentous images and an overblown sense of its own importance. Take, for one tiny example, the lighting of the beacons between Gondor and Minas Tirith. This could have been accomplished quickly and simply, but Jackson chooses to swoop from mountain-top to mountain-top, showing beacon after beacon being lit and doing even more for the New Zealand tourist industry. It is overblown and, crucially, it is without dramatic purpose.

Such moments are legion and they are symptomatic of the trilogy’s greatest weakness: there is no economy in these films.

Jackson’s only rule appears to be that more really is more. Longer even than its predecessors, The Return of the King stretches interminably, lingering over minutiae and diluting any excitement or tension in the story through repetition. How often, to take another random example, did Sam need to smack Gollum before the director felt the point was made and the audience finally understood that irritating little hobbit didn’t trust the whiny little ring-freak?

A knock-on effect of this unbalanced storytelling has been the shrinking of the characters. None of them make an impact as human (or whatever) beings. McKellen does his best as Gandalf, chewing the scenery and kicking ass impressively, but Aragorn’s (Mortensen) love stories are bloodless and without real passion. Frodo (Wood) is a moon-faced whiner; throughout the trilogy Wood has looked more like a teenager asked to tidy his room than a man with a terrible burden. Perhaps only Faramir (Wenham) and his father Denethor (Noble) give us a sense of real, though twisted, human emotions.

Much of this could have been forgiven if the film had something interesting to say: if there were, at its heart, something profound.

It doesn’t.

Through all their adventures, the hobbits can imagine nothing better than returning to the bourgeois Tellytubbyland that is The Shire and nestling back into the conservative little holes in the ground that they had to be winkled out of in the first film. Facing the wonders of the world they repeatedly eulogise their rural, Luddite, idyll. It is more than irritating, it betrays the essentially backward-looking nature of these films. Insofar as they say anything, they play into that increasingly common malaise – nostalgia for a fake, bucolic past.

Nor does the film possess moral or intellectual complexity. The good are blessed, the bad are wicked and that’s just the way it is. No lost souls are redeemed and no truly good men are corrupted. The dead hand of Tolkien’s moral absolutism weighs heavily on all the action. The literal (since Saruman has been banished) facelessness of evil in The Return of the King seems appealing. It is comforting to believe that our enemies are simply wicked – that way we can dispose of them without a stain on our conscience. They get what they deserve.

In the real world, however, where people just like you and I are willing to strap explosives to their chests and kill themselves to strike at those they hate, bad things happen for a reason. In our tribal and divided world, The Lord of the Rings’ black- and-white morality isn’t just quaint: it’s dangerous and wrong-headed. The fact that one man’s terrorist or dictator is another man’s freedom fighter or national hero has become a cliché, but it remains true. Even on rare occasions when the bad guy stands under a banner marked “wicked – please kick”, tackling evil always has a cost to the innocent. Sauron’s orcs may be dispensable cannon fodder, born to be bad like their master, but in real life ordinary people suffer when monsters are dethroned. One might want to argue that such suffering is a price worth paying but what one should not do, even in a fairytale, is ignore the price altogether.

That’s not to say that there aren’t enjoyable moments in The Return of the King – it is the most accomplished of the three films and, when there are fewest hobbits on the screen, there is some tremendous action. The battle scenes are done on a vast and spectacular scale. The catapult exchanges that open the battle for Minas Tirith are jawdropping. There are thrills, but because I never felt I knew or cared for the characters on the screen, I was never involved in the action or invested in the outcome. Perhaps, if I’d carried with me a knowledge or love of Tolkien’s novel, this might have been less of a problem. Having to judge these films on their own merits, however, they left me unmoved and disappointed.

The Return of the King can be admired as spectacle and lauded for its technical brilliance but I, for one, could not enjoy it.