As Rowan Atkinson returns to the stage in Oliver! Martin McGrath talks to him about his career, his relationship with Equity and how Cameron Mackintosh finally persuaded him to take the role of Fagin when he doesn’t like musicals and he once swore he’d never return to the West End or a long run in the theatre.

As Rowan Atkinson returns to the stage in Oliver! Martin McGrath talks to him about his career, his relationship with Equity and how Cameron Mackintosh finally persuaded him to take the role of Fagin when he doesn’t like musicals and he once swore he’d never return to the West End or a long run in the theatre.

As preparation for our meeting I did some research on Rowan Atkinson, reading the relatively few, and relatively short, interviews he has conducted with the national press in the last few years. It wasn’t an encouraging experience.

The journalists who wrote those articles paint a picture of a man who is intensely private and therefore reluctant to talk about anything for very long. The image that comes across is not of a rude man but one who is uncomfortable in the limelight, despite his enormous successes. It is clear he has little time for the usual rigmarole of celebrity and self-promotion. Many of the journalists who had preceded me seemed to have come away with precious little to write about.

As I was led up the steep steps and narrow passages of the backstage area of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, ducking between the layers of ersatz Dickensian London that form the backdrop for the latest production of Oliver! –in which Rowan has won rave reviews for his performance as Fagin – I was clutching my list of questions and wondering what sort of reception I was going to receive.

I needn’t have been concerned.

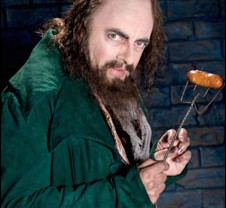

I caught Rowan between matinée and evening performances. He’s wearing half his costume and still in make-up, but he seems remarkably relaxed. I’m welcomed into his dressing room – which was refurbished just before the beginning of this production and is a surprisingly comfortable and spacious area. He jokes about the relative luxury he’s enjoying and far from the reticent, perhaps reluctant, interviewee I had been expecting, he’s happy to speak at length and with great passion on the issues that matter to him.

I first ask him about his membership of Equity. He’s been a constant and full-paying member of the union for thirty years. I ask him what Equity membership means to him.

“Well I’ve always believed in it really. I probably wasn’t much of a believer in the concept of the closed shop, as was, but I just like the idea of someone trying to watch over us in a business and profession that’s so complicated and so unpredictable and so geographically diverse. The very nature of entertainment and theatre is that almost anywhere can be a venue and almost anyone can be an employer, or self employed. It’s an extraordinary loose and unpredictable profession and it seems to me that it’s a good thing that there is someone trying to impose or negotiate a degree of regulation, even if it’s just in terms of hours you work and lunch breaks and the desire for even the most ordinary acting job to be reasonably paid. I just think it’s good that there’s an organisation that can draw this very disparate band of brothers and sisters together to try to maintain good and safe and reasonable working conditions.”

Working on Oliver! means working with a large cast of very young performers who are going to experience very different careers in a rapidly changing industry. I asked him what it was like working with all those young people and whether he felt he’d learned anything from the experience.

“The fantastic thing about this show is that it has brought home to me – something that I suppose I should have realised a long time ago – just what a great and worthy profession the job of acting is and how important it can be. But I think about it from the children’s point of view. We’ve got 140 children here in three companies who cycle through, each doing three shows at a time, and I look at it from their point of view and I think what a great experience it must be. The whole thing is like a huge and extravagant work experience where the young people are actually doing the same job as the adults – they’re not just making the tea – albeit with much more restrictive hours. You do see them getting tired. I have to say the idea of doing a day at school and then a show in the evening is not one that would appeal to me, but they only do it for a short run and then they have ten days off. From their point of view, feeling the discipline and the professionalism and the sense of community that a company as large and well organised as this one imbues people with is a very worthy thing. It’s an amazing thing for young people to do as long as they’re not exploited.”

In my research I’d read that Rowan’s previous experience of performing in a long run in the West End had left him swearing never to take on a long-term commitment to live performance ever again. I asked him what it was about his previous run in the West End that lead to his absence from the stage for two decades?

“I had a very bad experience with The Sneeze, these Chekhov plays with Timothy West and Cheryl Campbell in the 1980s. They were very successful but I just felt at the time at least that I’d made the mistake of extending from four months to six and it was six months of doing the same thing every night. I know there are people in the West End who will laugh at my recalcitrance. Someone who has been in Phantom of the Opera for 23 years, as some of them have, would laugh at my doubt about the process of working on a show for six months. But there was something, maybe it was the nature of the show, it was successful but I just found that it ground me down creatively. Maybe it was the nature of the material or something in the production. We had this very unfortunate thing with Cheryl Campbell, who fell ill after two or three months and we had her understudy for the rest of the run. The producer didn’t want to replace her and the understudy was fine but it was one of those things where the production was slightly teetering and there was the feeling of needing to reinvent the wheel with every performance when you hadn’t really enjoyed doing it the previous night. I couldn’t see what the point of this was. And as I’m a sort of creatively curious person, I’m always wanting to do something different, it was very difficult.”

I put it to him that he is also on record as having said that he didn’t like musicals. So how did he end up back in the West End, committed to a long run, and singing and dancing in a musical?

“Why am I here doing this? It is largely because of the role. There’s a letter here from me to Cameron, which Cameron kindly framed, in which I told him I didn’t want to play Fagin. He first asked me in 1993 and he talked about doing it for nine months or a year and I’d had that Chekhov experience and thought: over my dead body. So I went off the idea. Then I told him no again in 2007.

And then a year later, in 2008, I read an obituary of Paul Schofield. He was a very great man and his greatest work was done in the theatre. He’d done films and television and all those things but he was most conspicuous in the theatre. And it set me thinking that here was a whole medium in which I had a lot of experience but I hadn’t done it for 20 years. I didn’t want to get into my dotage thinking: God, if only I’d experienced that again, that simple intimacy between yourself and an audience that only a theatre can provide. I thought that I may have to grasp the nettle and, in the end, roles like Fagin in productions as good and well-thought out in a venue as terrific as this place – built 60 years before Dickens wrote Oliver Twist – are very rare. The whole thing felt like something one would be foolish not to be part of if one had any inclination to play the role, so I grasped the nettle and rang Cameron on Good Friday.”

Cameron Mackintosh’s persistence and reputation seem to have had a significant influence on his decision.

“This is an exceptionally well-endowed show, it’s very good material, a very good director, a very good cast and, while I don’t know what anyone else is getting paid apart from myself, I assume it’s one where everyone is well looked after. Certainly Cameron Mackintosh is someone who has got a reputation for erring on the side of being generous, which is not always the case in the West End or with other producers.“

This production of Oliver! is notable for having had the parts of Nancy and Oliver cast through the television talent show I’d Do Anything. I asked Rowan whether he’d watched any of the programme and what he made of it as a way of selecting a performer to appear in a West End production. It’s a system of casting that has been very controversial with Equity members.

“I did see some of it. I can’t say that played a part in persuading me to take the role but I had seen it. I have to say I don’t think that those shows are the best way to select a person for a part in a West End show. I think that the standard auditions are better at finding out whether someone is competent to take on something a big and as complex as this. But we were very lucky. Jodie [Prenger, the winner of I’d Do Anything] has been fantastic. She’s worked very hard and the audiences and the kids in the show love her. So this is no criticism of her. I just think that the traditional auditions are the best way of picking people.”

As we’ve already noted, Rowan Atkinson is famous for his reluctance to step into the public eye and has avoided the exposure in the press that usually accompanies the kind of success he has enjoyed. One issue, however, seems to have drawn him into the public arena again and again over recent years – freedom of speech. He’s been a vigorous campaigner against the Labour government’s attempts to restrict free speech through bills such as the Race and Religious Hatred Bill – which would have created the offence of “Incitement to Religious Hatred”, a measure which would effectively have made it a crime to make fun of, or criticise, any religious belief.

Rowan is quick to make the point that he’s opposed to racism: “It’s ridiculous and patently irrational to criticise someone because of their race” but believes that the freedom to criticise ideas (whether they are articles of religious faith or not) is, and should remain, a basic right in a free society.

“The way the government approach these things is to find groups they can work with, groups they think they can deliver the support of a certain community or group, and then offer them deals that will tie them to their policy. With the Race and Religious Hatred Bill the government signed up the Muslim Council of Britain and they persuaded them, they persuaded each other, I suppose, that this law was a good idea. Of course these groups want to be shown to be delivering something for their people and the politicians are hoping to line up their support, it hardly matters whether the law is any good or not.”

It was the scope of the legislation, not its purpose that stirred Atkinson.

“The bill as it was first proposed, though thankfully not as it was finally passed, would have potentially made any criticism of religious belief a criminal offence. I think the effect would have been intimidating. Even if, as the government had promised, they didn’t mean the law to apply to the arts, I think it would have been a pressure on performers. I think it would have led to self-censorship.”

And Rowan rejected the idea that religious groups should have a right not to be offended.

“You can’t choose your race, but you can choose our religion. Religious beliefs are ideas – however deeply held – and it can’t be right that ideas should be immune from criticism. The right to free speech – the right to offend – seems to me to be far more important than the right of tiny minorities of religious fundamentalists not to be offended.”

Having campaigned successfully to get the government to amend its legislation on the religious hatred bill, Rowan Atkinson found himself fighting a similar cause just a few months later. This time the government, working with groups promoting fairer treatment for gay and lesbian groups, proposed to create an “anti-homophobia” law.

“That was strange. Suddenly many of the people I’d been campaigning with to preserve the right to be critical of religions were now attacking me because I was against this new law. But I always felt that I was campaigning for the same thing – free speech.”

Comedians should be able to make jokes about whatever subject they want to mock, Rowan said. If they go too far, people won’t laugh and won’t watch them. “There should be no subject about which you cannot make jokes.”

I asked him , given the controversy he’d been involved in and some of the criticism that he’d attracted for his stance, whether he’d worried about taking on the role of Fagin – a role that has sometimes been controversial for its portrayal of a Jewish character in a stereotypical light?

“I’d be lying if I said it hadn’t crossed my mind, but no I never thought about not taking the part because of that. I think you have to make a distinction between Fagin in the novel – which I think you might criticise for having some of those stereotypical elements that would have been taken for granted in Dickens’ time – and the Fagin in Oliver!. Lionel Bart, who was Jewish himself, made his Fagin a much more sympathetic character. And also I could see in the part how I would play him and I felt that it didn’t contain those elements, so I never worried about the part in that way. There were lots of other things I worried about, but not that.”

Finally I ask him whether, after success in television, film and theatre, he still had ambitions left. He laughs.

“No, not really. I’ve never been ambitious like that. There have been things I’ve wanted to do, that I’ve enjoyed doing and I’ve got plans for the future. We’re working on a new film that we intend to make next year. But I’ve enjoyed being back in the theatre and I’d like to do more. There are definitely parts I’d like to play. But I don’t think I’d do another long run, even as long as this, even though I’ve enjoyed it. A few weeks in somewhere like the Donmar would be great!”

My stock of questions has been depleted but time has flown by – the interview has taken much longer than intended, but Rowan has been incredibly generous with his time. I pack my things up and as I make to leave I can’t help admiring the striking oil painting of two Formula One cars on his dressing room wall. Rowan is famously a fan of motor racing and of fast cars.

“It’s a bit of a cheat,” Rowan says of the painting. “It shows Nigel Mansell leading the race, it’s the Hungarian Grand Prix in 1992, but he actually finished second to Senna. You can’t always trust paintings.”

It’s only as we make our way back through the theatre’s plywood streets of the Dickensian London portrayed in Oliver! that it occurs to me how perfectly that statement summed up my experience of the interview. In person Rowan Atkinson proved to be nothing like the way he has been painted in the press.