I was just reminded of this after a random comment on Twitter (hi @redrichie). I wrote this review back in 2014 for Arcfinity. The row over inequality hasn’t moved on much and, reading it back, I think some of the things I said are still relevant – we are certainly no closer to a political response to growing inequality and mainstream economics seems to have slipped back into its comfortable irrelevance.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital In The Twenty-First Century is a number of things. It is, most obviously, a forceful argument in favour of putting inequality – a subject long plagued by “an abundance of prejudice and a paucity of fact” – back at the heart of intellectual and political debate. In addition, and almost as importantly, it is giant single-fingered salute to economics as it is most commonly done. Capital is a trenchant criticism of the way in which the study of economics has become dislocated from history and reality, focussed instead on abstract models and “laws” that seek to universalise the particular and the specific. Piketty’s theory is based on carefully collected data and lived human experience – a book that seems to spend as much time considering what can be learned from the novels of Austen and de Balzac as from the theories of other economists. And Capital is also – and this is not something to be lightly dismissed – a social sensation. A seven-hundred-plus-page economic thesis has become an international bestseller and the subject of near endless debate, attracting praise and opprobrium in about equal measure.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital In The Twenty-First Century is a number of things. It is, most obviously, a forceful argument in favour of putting inequality – a subject long plagued by “an abundance of prejudice and a paucity of fact” – back at the heart of intellectual and political debate. In addition, and almost as importantly, it is giant single-fingered salute to economics as it is most commonly done. Capital is a trenchant criticism of the way in which the study of economics has become dislocated from history and reality, focussed instead on abstract models and “laws” that seek to universalise the particular and the specific. Piketty’s theory is based on carefully collected data and lived human experience – a book that seems to spend as much time considering what can be learned from the novels of Austen and de Balzac as from the theories of other economists. And Capital is also – and this is not something to be lightly dismissed – a social sensation. A seven-hundred-plus-page economic thesis has become an international bestseller and the subject of near endless debate, attracting praise and opprobrium in about equal measure.

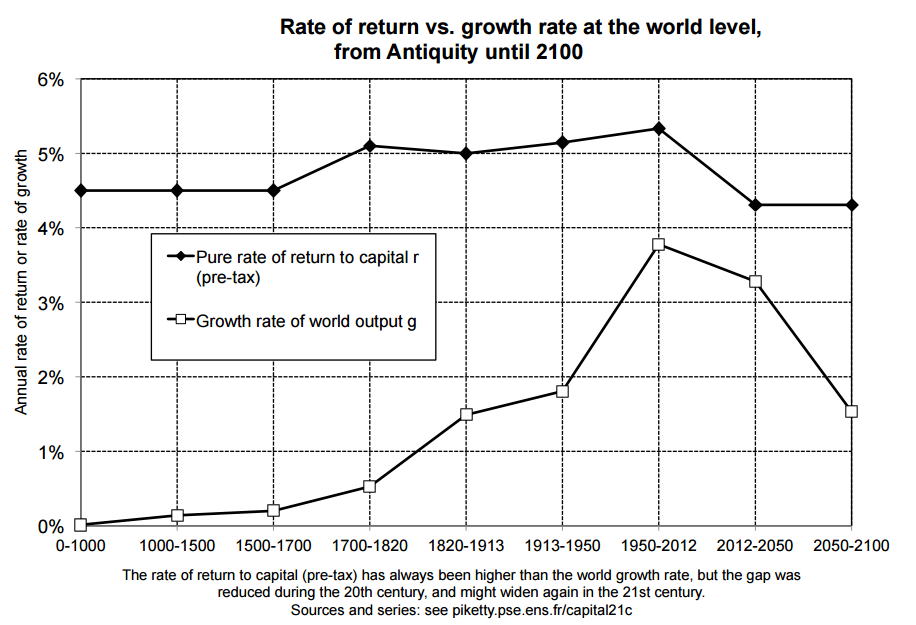

The core of Piketty’s argument is relatively straightforward – the heft of the book is in his meticulous support of his case with facts and figures. At the heart of the book is the notion that when the rate of return on invested capital is higher than the rate at which the wider economy is growing (summarised in the books only crucial equation “r > g”) then wealth concentrates in the hands of those who are already rich. Their fortunes grow more quickly than the rest of the economy so they come to own an ever higher percentage of the available resources. This condition held throughout most of the 1800s and culminated in the belle epoque –that period at the birth of the Twentieth Century in which vast, arbitrary fortunes created unsustainably unequal societies that tore themselves apart amidst the trauma of world wars and economic crashes.

What came next was without precedent. Economic expansion has two elements – population change and purely economic growth. We know, from the size of the population and economy when we started keeping detailed records that growth for most of human history cannot have averaged more than 0.1 percent – otherwise there would be many more people making many more things in the modern world. This means that most generations, certainly until 1800, lived in societies where growth was imperceptible – cumulatively below 5 percent in an entire lifetime. Those born in the Twentieth Century, however, saw extraordinary demographic and economic growth – averaging around 1.5 percent every year, and higher still (3-4 percent per annum) in the three post-war decades. Economies doubled in size and then more than doubled again during a single lifetime. The world was transformed before the eyes of individuals and rapid expansion opened opportunities for them to rise through society. Crucially, the economy grew faster than the return on investments, meaning that the relative size of inherited or accumulated fortunes were constantly eroded (and were further undermined by the novelty of sustained, general inflation) so that wealth became somewhat less concentrated.

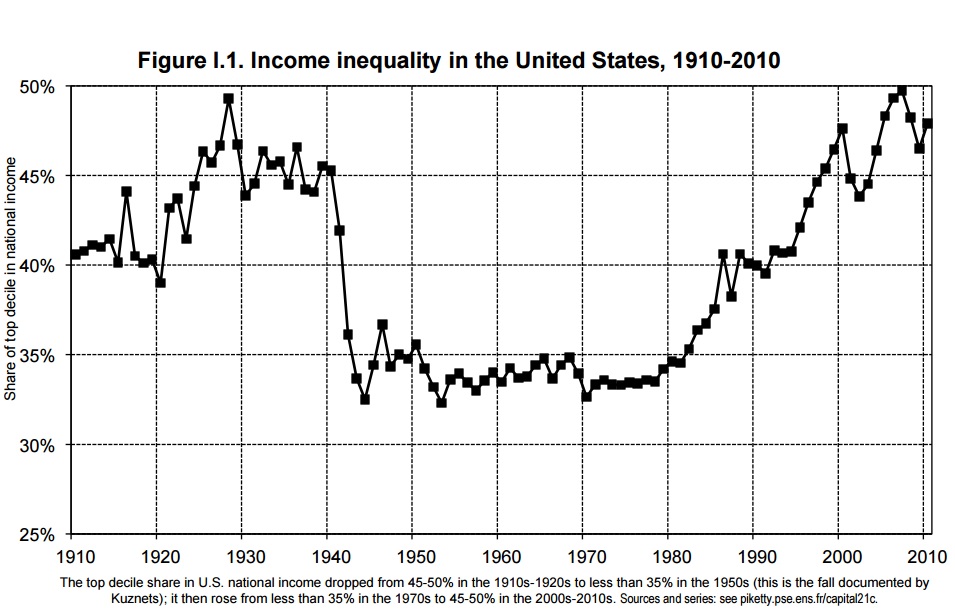

To be sure, in general, the poorest half of society started the Twentieth Century with almost no share of their nations’ wealth and ended it in more or less the same state. At the same time the richest tenth – and in particular the richest one hundredth – of society continued to enjoy a significant concentration of wealth. But the scale of inequality did decline. The rich became comparatively less rich and a middle class (that 40 percent of the population between the bottom half and the top tenth) carved out for themselves, for the first time, a significant proportion of the national wealth.

But that era is over. It ended in the 1970s and, Piketty argues, it is unlikely to return. We live now in an era of slowing growth. The demographic explosion is tailing off, with many developed nations already experiencing stable or even slightly declining populations. The economic growth inspired by post-war reconstruction and rapid technological advance is unlikely to return. The returns on invested capital now outstrip economic growth and those who are already rich are becoming richer. The fragile wealth accumulated by the middle class is being eroded.

Piketty then sets himself to address that most science fictional question: what happens if this goes on?

His conclusion is that our future is likely to look more like the Nineteenth Century than the Twentieth. America is already well on the way towards concentrations of wealth that have not been seen since before the First World War and Europe is not far behind. The result, Piketty fears, will be “economic, social, and political disequilibria of considerable magnitude, not only between but within countries—disequilibria that inevitably call to mind the Ricardian apocalypse.” The concentration of wealth and power in the hands of those who possess it simply because of the good fortune of their birth is antithetical to the meritocratic mythology of our existing democracies. The evidence of history is that such top-heavy societies are both economically and politically unsustainable and that their ends are violent.

Can we avoid this future? Piketty makes the case that taxation targeted at the few (a progressive systems that targets inherited wealth through an annual global wealth tax) could slow or reverse the concentration of capital. The point he makes, which seems to me a fair one, is that progressive taxation, accompanied by a change in attitude towards wealth, tamed capital after the Second World War and could do so again.

The problem, however, as Piketty is aware, is the absence of political will and the disconnection between the study of economics and the needs of our society. It took a series of world-changing shocks to shift the economics of the Twentieth Century – it is not entirely clear if our society could survive a similar run of conflict and disaster today. Certainly no one could wish to endure suffering on a similar scale. There is nothing inevitable about inequality, it is deeply political and “shaped by the way economic, social, and political actors view what is just and what is not” but that does not mean that making the world less unequal is easy or likely. This book is a noble attempt, not without its flaws, to reconnect the purpose of economics with the lived experience of people. However, as the first reaction of many economists has already demonstrated, they would rather reduce the argument to debates about the internal consistency of their theoretical models than engage with empirical data and human experience.

Piketty recently insisted that he is not a pessimist, and that his book should not be considered pessimistic, but it is difficult to walk away from Capital In The Twenty-First Century without feeling that we are heading towards a dangerous future without the will or the tools necessary to avoid disaster.