Those she talked to who wanted the store to come here had hardly embraced evil. They talked about how hard things were, how they needed to shop more cheaply without spending a lot of money on petrol, how they and their relatives needed the jobs Sovo would provide. There was something of a class divide there. Those who weren’t well off tended to back the store on the basis of economic survival.

As Lizzie had seen so many times with victims, the harder your life had been, the harder it was to give yourself room for ethical choices.

(Witches of Lychford, p103)

“Victims” – remember the word “victims”.

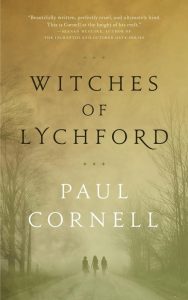

I’m going to start with two apologies – or one apology and one partial apology. First, I apologise for starting a review with a longish quote from the book I am reviewing. I’ve always thought this is a bit lazy, but it’s no exaggeration to say that these two paragraphs made me so angry – punch walls and slap innocent bystanders angry – that I thought it was worth pulling them out and considering them in detail. And, second, I apologise, in advance for writing a review that won’t talk much about the plot, writing or anything else within the covers of Paul Cornell’s Witches Of Lychford except the way it talks about class.

Actually, I’m not really apologising for that one. Consider it more of a warning about what is to come.

I don’t imagine Paul Cornell will be bothered that I was annoyed by his book. This little novella has been very popular, warmly reviewed, award nominated and the basis for not just a sequel but also a soon-to-be-released third book. Lychford and its witches appear to becoming the foundation of an ongoing series. And Cornell writes well enough – his style is restrained and understated (English, you might even say), there’s nowhere where the writing really takes flight stylistically, but nowhere either where you’d be offended by the gratuitously stupid. If you like this sort of thing, and people evidently do, there’s no reason why you won’t like this.

I don’t imagine Paul Cornell will be bothered that I was annoyed by his book. This little novella has been very popular, warmly reviewed, award nominated and the basis for not just a sequel but also a soon-to-be-released third book. Lychford and its witches appear to becoming the foundation of an ongoing series. And Cornell writes well enough – his style is restrained and understated (English, you might even say), there’s nowhere where the writing really takes flight stylistically, but nowhere either where you’d be offended by the gratuitously stupid. If you like this sort of thing, and people evidently do, there’s no reason why you won’t like this.

In Witches of Lychford an idyllic English market town, nestled in the Cotswolds, faces an existential threat – the arrival of Sovo, a big-brand supermarket. But not just any big-brand supermarket. Sovo is, literally, the work of the devil and the only people that can stop the defiling of Lychford – this other Eden, this demi-paradise – are three women of various varieties of witchiness: old-style, new age and Church of England.

The threat represented by Sovo is not just the coming of an external evil. As the passage above makes clear, there is an enemy within. People are being seduced by its promises (and its associated cash). The mayor has been corrupted, good citizens are being won over and, on the northern edge of the town, in the gloomy, distasteful housing estate (“The Backs”) the unethical poor are rumbling discontentedly. We don’t actually see many of these people in Cornell’s novella, his Lychford focuses very firmly on the middle class, but those that we do see are weak and corruptible: like Jade Lucas, who will do anything including, literally, kissing the arse of the devil, for a slightly better job with Sovo.

Now, Cornell’s position is clear. The intrusion of this edifice of global capital into his England, (this precious stone set in a silver sea) is a BAD thing – even without the accompanying diablerie. His protagonists – especially the old witch Judith and the vicar Lizzie – are fighting to preserve the good and ancient order of Lychford with the church at the centre of the town, local boutique shops serving a discerning citizenry, respected ancient boundaries and the worthies of the town council (not a political party in sight) making the decisions that matter.

The poor, in falling for the devilment and the tainted silver offered by Sovo, are not necessarily evil, but they are weak, ignorant of what is really at stake and therefore incapable of resistance. They do not appreciate what really matters about Lychford. They are willing to surrender its history, traditions and order for fripperies: a wage, a place to live, ambitions to be more than shadows banished to the periphery of their town and this story. Their need for the basics of survival leaves them without the necessary backbone to make the ethical choice, thus someone must do the right thing for them. Someone smart, someone with the right background, someone who can be trusted to preserve order.

This mixture of lack of respect and paternalism made me very angry.

Yes, it’s true, poverty limits the choices and opportunities of those who experience it, but it is also true that in these communities people work hardest to make the right choices for themselves and for their families. It is poor communities that bring their kids up right, teaching them to respect each other and look out for each other, and do so despite every day being a struggle to make basic ends meet. It is precisely these communities where people make the bravest ethical and political choices, where they show the greatest strength, despite having least and it costing them more. And, of course, some fail but failure is not unique to their class.

It has, in recent history, been those who have had the most room for ethical choices – an infinite number of rooms, all en suite and with pretty bay windows looking over unspoilt rolling countryside – who behaved selfishly, who enthusiastically consented to the destruction of social safety nets and enriched themselves through the sale of public assets. It was not the poor on council estates who created the instruments of economic destruction that lead us to a decade of austerity and lost opportunity. It has, over and over again, been the comfortable and secure – those who can afford to buy nice houses in the ancient heart of Cotswold market towns – that have made the immoral choices that undermined the social values they claim to value so highly. And all the while they have continued preaching to the poor about their lack of moral fibre.

The poor are not just victims and the choices they make are not born just from their weakness. The truly strange thing about Cornell’s Lychford isn’t the presence of witches and demons and fairies. The truly strange thing is that the author can imagine that the situation is so bad that a large number of the town’s citizens might be willing to make a deal with the devil, but he can’t imagine that their choice might be a rational response to their discontent at the shitty end of the stick that they get from the traditional order that his protagonists are fighting so hard to defend. If he can imagine that the crappy jobs offered by an evil global corporation can be so appealing to the inhabitants of The Backs, why can’t he imagine that the cosy status quo of Lychford needs a kick up the arse rather than just assume that these poor souls are too weak, too ignorant or too lazy to do the right thing?

The Witches of Lychford ends with order restored, of course. The town has been saved from the evil of a supermarket opening on its doorstep and the rest of the world from the hell it would have unleashed. Lizzie, the vicar, has her faith back and Judith, the old witch, has Autumn as an apprentice to whom she can pass her ancient wisdom. All is restored and Lychford can stay just as it has always been.

Except, what about those of this happy breed of men who are still huddled on the edge of town in their grim council houses? Where will they work? How will they feed themselves? How will they live in this brave old world of their gentile Cotswolds’ dormitory town?

Cornell never tells us. The people of The Backs are entirely absent from the denouement of Witches of Lychford. It’s almost as if they never really mattered – almost as if this book was really only about preserving a certain type of English house “against the envy of less happier lands” and the depredations of our unhappy present.

There is one moment in the epilogue that is, I think, revealing. Cummings, the devilish supermarket manager, returns to tempt Lizzie in her church. There is a pile of money – tainted to be sure, but offered without strings – with which Lizzie could do good, could help those poor souls about whom she cares so much. All she has to do is take it and use it. Instead, she burns the cash in a show of defiance, to spite Cummings and his works. The idea that she might ask the poor what they want to do with the money, that they might be capable of making an informed decision for themselves, never seems to occur to anyone. Things go back to the way they were, Lizzie promises to hold a bingo night to raise some cash – knowing it will never be enough.

The Witches of Lychford has been well received. Its comfortable vision of middle Englishness has clearly struck a chord with readers and reviewers. I’m sure that Cornell and his novella’s heart are in the right place. He doesn’t really want to write poor people out of the world. I’m sure, too, that he’s sincere in his argument that the defence of traditional communities against the unfettered trampling of global big business is the decent, progressive thing to do. The problem is that the alternative for the hidden masses that so lightly impinge on his story is a return to a society where they are seen but not heard, not paid attention or money and not much cared about.

Lychford is a lovely place to live. A place worth defending. It just isn’t a place for everyone.