Jeremy Corbyn set out his 10 point policy plan today – with lots of good intentions in it, though it didn’t quite address the concerns I have about Corbyn offering actual detailed policies – it remained a bit vague. In a speech full of non-specific hand-waving the biggest blur was how it was all to be paid for. I’m a big fan of ambitious investment plans for government, but they do have to be realistic, and Corbyn’s numbers today are pretty wild.

In 2015 the size of the UK economy, measured by nominal GDP, was around £2.2trillion. Corbyn has just promised to spend £500million (half a trillion) over 10 years through a National Investment bank.

This is a pretty astonishing number. That’s a sustained, additional, annual government spending of 2.5% of the current (and since we’re not looking at any economic growth over the next year or two – the near future) size of the UK economy – which is pretty unprecedented. In the crisis year of 2008, the Obama administration dropped that level of money into the US economy – but only for one year.

Asked how he would pay for this investment, Corbyn said it would be paid for by “a stronger economy and by cracking down on tax evasion”.

Since 1956, the UK has managed an average annual growth of 2.46% (this, of course, disguises significant fluctuations, from almost 10% per year in 1973 to -6.1 in 2009 – GDP growth details here). So, the extra spending Corbyn proposed today is slightly larger than the historic rate of economic growth in the UK economy.

Corbyn’s planned investment would probably create faster economic growth (outside factors such as oil prices and international wars being equal) but if it going to raise the money Corbyn needs to pay for a programme of investment of the size propose today, most or all of the growth in the economy would have to be recouped by taxation. Or, since Corbyn did not announce increased taxation today, the UK economy would have to grow consistently at over 6% per year for a decade to fund Corbyn’s plans. Some European economies (Ireland, Romania and Malta), bouncing back from very low levels, are predicted to manage annual growth rates of over 4% in 2016, but no one expects this to be sustained over a significant period. That level of sustained growth in a developed economy would be nothing short of miraculous.

The other option Corbyn discussed was reducing tax evasion.

Every government promises to crack down on tax evasion, and while I’m not denying Corbyn’s enthusiasm to achieve his goal, I’m less convinced that the money he needs is there waiting to be tapped. Yes, it is outrageous that firms and individuals can exploit national and international rules to minimise their tax payments, but the complexity of closing tax loopholes and the mobility of capital makes boosting government revenues more difficult than it sounds. Some money might be available, but it’s not likely to the huge sums that some observers have claimed.

HMRC estimates the current “tax gap” at around £34bn per year – of which about half is due to tax fraud – this is a significant sum but some put the gap much higher. Richard Murphy (formerly a Corbyn adviser) has estimatied a tax gap of £119bn – which would more than cover Corbyn’s investment plans, if it could be collected. Murphy’s figure include £18bn tax debt (money we know is owed but those in debt are struggling/avoiding repayment), £19bn estimated in tax avoidance (using legal means to lower tax bill) and around £82bn estimated in tax evasion (deliberate, unlawful actions to avoid tax).

But how much of this is recoverable?

That’s much harder to say. Murphy, for example, offers no estimate of how much of that £119bn might be recovered. It certainly isn’t the whole of that figure. It might not be very much of it at all. [ADDENDUM: I should have spotted that in a separate report Murphy has estimated that £20bn is realistically recoverable for a cost of around £1bn – so net to the exchequer of £19bn.]

“Tax debt” is already pursued and most of what can reasonably be recovered is probably collected, though it’s possible there’s some room for squeezing more from the system.

It might also be possible to change the laws to collect all of the money avoided using legal means – “tax avoidance” – but, again, this seems unlikely. There is a literal army of tax lawyers and accountants whose working lives are devoted to exploiting loopholes in tax laws and they are unlikely to go away. High profile cases – such as Google, Facebook, Starbucks and other corporations can be pursued through legal changes or shamed via public opinion, but it’s unlikely to change their basic desire to limit the tax they pay. In the complex field of international taxation, watertight legislation is probably a pipedream and international agreements are difficult to envisage. Some fraction of the money lost to avoidance might be recovered, but it will not be easy and how much is uncertain.

On deliberate tax evasion – even if Murphy’s very high estimate of what he calls “shadow economy” (£82bn) is correct – much of this money is related to very small enterprises – individual builders taking “cash-in-hand”, corner shops (knowingly or unknowingly) selling goods that have been imported in ways that avoid paying duty or counterfeit items on which no VAT is collected or wealthy individuals who knowingly and criminally hide their earnings. This money can, and should, be pursued but collecting a significant proportion of it is likely to be very difficult. I think there’s some value in Murphy’s figures as a very rough estimate of off-book economic activity, but I’m less convinced of its use as a measure of collectable tax liabilities.

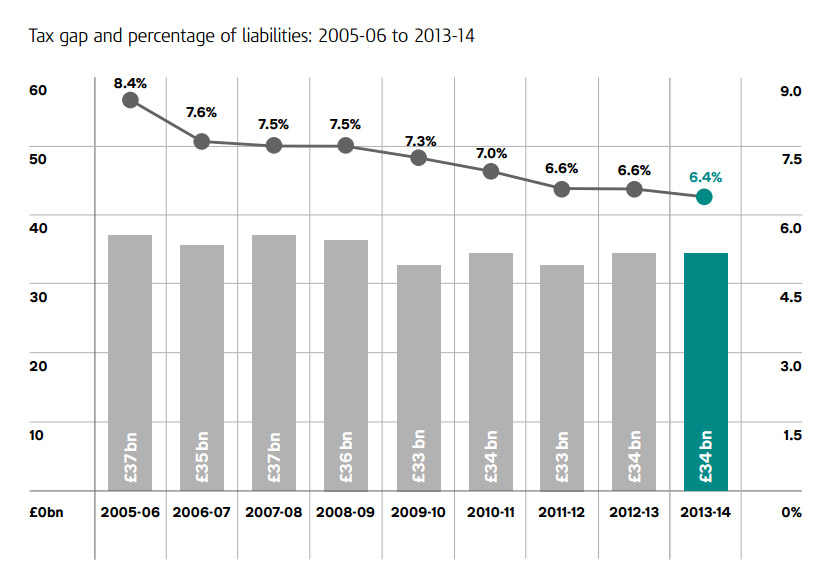

The HMRC measurement of the tax gap seems the more realistic figure in terms of money that might be collected and to be more useful for policy makers. But the HMRC figures contain some further bad news for the hopes of finding an untapped pool of money to pay of Corbyn’s plans. There has already been significant success in reducing the tax gap as a proportion tax liabilities – it fell by almost a quarter between 2005-6 and 2013-14 (HMRC chart below). The low hanging fruit has already been picked, further reductions are going to be more difficult and more expensive to achieve.

In any case, the idea that all owed tax is recoverable is highly dubious. If, as I suspect, the HMRC figure of £36bn is the more accurate estimate of actually measurable tax liabilities, recovering a third of that money would be an extraordinary (and unlikely) achievement. Whatever is recovered will be a fraction of what is needed for Corbyn’s plans – even Murphy’s ambitious estimate of £19bn would not be enough.

If we, generously, assume that the government could immediately recover that full £19bn a year estimated by Murphy and maintained a well above average growth rate of 4% a year for a decade, then a Corbyn government might just raise the money it seeks. But it needs to be noted, the UK economy since WW2 has never sustained 4% growth for more than two or three years and each instance of boom was accompanied by a sharp bust – a year or more of recession or stagnation.

Both the scale of tax recovery and the estimations of growth stretch credulity beyond breaking point. The idea that Corbyn’s plans could be paid for by growth and tax recovery alone is fantasy.

That leaves Corbyn three further options – increased taxes, higher borrowing or printing money. As noted, Corbyn mentioned tax today but did not propose significant tax rises. The other two options were not mentioned by Corbyn today – though I suspect the details of McDonnell’s thinking focus primarily on printing money. I’ve heard someone close to him describe the Bank of England as the “magic money tree”. But printing huge sums of money could have serious economic consequences – most obviously higher inflation – that could make achieving the growth Corbyn (and McDonnell) needs to achieve more difficult. It would also raise the cost of Corbyn’s proposals, requiring even more money to be raised/printed – as well as punishing savers, mostly pensioners. There is room for modestly higher inflation in the UK economy – it is a plausible means of reducing the burden of national debt – but the size of Corbyn’s proposals are such that it is difficult to imagine the pressures being controlled.

By contrast, Owen Smith’s plans are also very ambitious (I have doubts that either Smith or Corbyn can realistically deliver the programmes they have set out) but at least he costed his plans in detail – with proposals for progressive taxation to redistribute wealth (a 50p tax rate, inheritance and corporation tax rises and a wealth tax) and his £200bn (over five years) investment bank programme is explicitly to be funded by a government bond sale – taking advantage of very low interest rates to borrow money to invest. Both tax rises and increasing debt are likely to be attacked by the Tories, but at least the proposals are realistic and broadly defensible. Labour campaigners and spokespersons trying to defend Corbyn’s proposals are likely to be shredded, sent “naked into the negotiating chamber” as Bevan had it.

Corbyn’s plans are fantastical and his refusal to confront how they might be paid for is, frankly, either lazy or cowardly.

I’ve made this point before, but Corbyn’s pitch is that he is a radical who wants to reshape the conversation about politics in the United Kingdom. But, time and again, his policy proposals have been limp and poorly thought through and his supposed radicalism has evaporated on closer investigation. There is nothing radical in pretending that a magic wand can be waved and that a “New Jerusalem” can be constructed without the bills being paid.