The thing that I like best about Chris Beckett’s short stories in general, and this new collection, The Peacock Cloak, in particular is the rage that is bubbling under the surface and that occasionally erupts from the page.

The thing that I like best about Chris Beckett’s short stories in general, and this new collection, The Peacock Cloak, in particular is the rage that is bubbling under the surface and that occasionally erupts from the page.

Not all the stories grip you by the throat, “Atomic Truth”, the first in this collection, is a story in which a young woman reaches a moment of epiphany while brushing briefly against the life of a man with mental illness in a near future London. There’s little enough going on the surface, but underneath there’s a sense of something deeply wrong.

Other stories are more straightforwardly furious. In “Johnny’s New Job” Beckett, a trained social worker, rips into the way we use public servants as scapegoats, turning the way we burden them with impossible expectations while denying them the resources necessary to do their jobs into a bitter little near-future parable of witch-hunting turned into way of life. In “Greenland”, disastrous global warming and the desperation of those being exploited as illegal immigrants in a near future United Kingdom intersect and lead the protagonist to disaster. Environmental disaster raises its head again in “Rat Island”, where the fragility of the immersed, distracted society glimpsed in “Atomic Truth”[ref]And in the earlier “Piccadilly Circus” – collected in The Turing Test[/ref] is revealed and a father, a senior civil servant, burdens his son with a truth he himself cannot face. And then there’s “Our Land” – in which Beckett uses inter-dimensional slipperiness to turn England into an ersatz Palestine, where “returning” Celts have displaced the “native English”, establishing settlements and inciting hatred and violence.

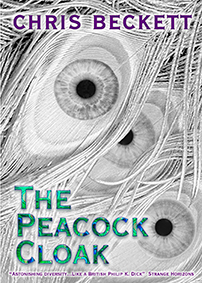

This book has a tough act to follow. Beckett’s last short story collection, The Turing Test (2008) won him the Edge Hill Prize – beating works by a number of much-lauded “literary” authors. The standard here is not quite that high, I think, though that’s not to suggest that this is a weak collection. It contains some excellent stories but also a few that felt familiar. “Two Thieves” is a tale of greed bringing hapless explorers low, “The Caramel Forest” has a young girl seeking escape from domestic troubles on an alien planet and in “The Peacock Cloak” a virtual god meets his maker.

There are, however, far more stories that bristle and seethe. For me the stand-outs are the previously mentioned “Atomic Truth”, “The Desiccated Man” – in which a greedy, misanthropic spaceman does something vile and fails to understand his sin – and “The Famous Cave Paintings on Isolus 9” in which Beckett comes closest to channelling the existential terror that is sometimes found in the work of the American author with whom he is most often compare: Philip K Dick.

Taken as a whole, a reader with a weak constitution might find that there’s a certain grimness running through Beckett’s work in this collection. There’s precious little hope, not much joy and no chance of redemption. But that, I think, would be to miss the point. Chris Beckett is an angry writer and we should be grateful for it.