I’m a strong supporter of Labour’s links with trade unions and the work of unions in general. I’ve worked for two different unions (more than ten years, in total) and the first thing I do in a new workplace is dig out the details of the recognised trade union – not always an easy job – and sign up. I’m a long-term member of the NUJ (my professional union) but I’ve also been a member of Unison, GMB and Amicus amongst others over the years.

Unions play a vital role in society and ordinary people need stronger unions. We live in an era where power has swung dramatically in favour of employers: jobs are outsourced, wages are falling, employment rights have been undermined, the public sector – the final bastion of mass union membership – is being more than decimated. We are at precisely at the moment when unions should be at the forefront of a battle on behalf of working people.

But, for far too long, the union movement has been pointing in the wrong direction. The relationship with the Labour Party is important – crucial, even – but unions’ real political strength never came from the internal wrangling of Labour politics. Generations of general secretaries have obsessed over getting their way at Labour Party Conference or in the National Executive, but all the while the real source of their influence has been slipping through their fingers.

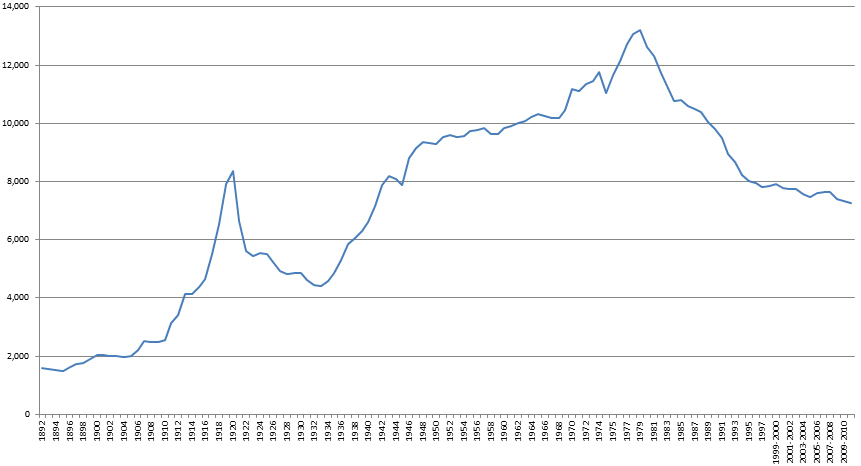

The graph below shows the number of union members in the UK since 1890s. The precipitous decline since the late 1970s is obvious– from over 13million to below 7million.

But the real picture is actually far worse. Even though it seems that unions have managed to, roughly, stabilise membership levels since the late 1990s – thanks to a renewed emphasis on recruitment through smart initiatives like Unionlearn – the fact is that there has been a rapid growth in the number of people employed. So this period of apparent levelling off of union membership numbers has actually seen union density (the proportion of union members as part of the whole UK workforce) fall from almost 33% in 1994 to just 26% in 2012. Out of a total workforce of more than 25 million, only 6.5 million UK employees are in a union. And the figures are far worse in the private sector – unions are represented in only one in five private workplaces and only one in every eight private sector workers belongs to a union. The picture for young workers is dismal – density has halved since 1995 so that in 2012 fewer than 3% of 16-19 year olds and 10% of 20-24 year old workers were union members.

Year Union Density (%)

1995 32.4

1996 31.4

1997 30.7

1998 29.9

1999 29.7

2000 29.8

2001 29.3

2002 28.8

2003 29.3

2004 28.8

2005 28.6

2006 28.3

2007 28.0

2008 27.4

2009 27.4

2010 26.6

2011 26.0

2012 26.0

It is this rapid and sustained decline in union membership – not any rightward shift in the Labour Party (though that has also happened) – that has done the most to rob unions of the influence they used to exercise.

Unions were slow to respond to this decline and much of their response has been wrongheaded.

First they pretended the decline wasn’t happening, continuing to throw their weight around in fights they could not win. Then they pinned their hopes on turning back the clock – holding out for the repeal of anti-union legislation and dreaming of a return to the closed shop. And then they began a long period of consolidation. Small professional unions disappeared, merging into larger conglomerates and they, in turn, merged with each other. There were 800 separate unions after the Second World War, in 1976 there were 527, today there are around 170 registered with the Certification Officer (though many are tiny); 54 of these are TUC members (16 are affiliated to Labour). Around half of all union members (3.5m) are concentrated in just three huge agglomerations: Unite, Unison and the GMB.

This process of merger seemed like a smart move – a way of cutting costs and concentrating power in a period of decline. In truth, however, it’s been a sham – preserving an image of corporate strength while unions’ actual ability to represent and defend their members has crumbled. Worse, it has reinforced the notion that things can go on as they always have done, just at the point when the environment was changing faster than ever.

The workplace has become more fragmented and workers’ experiences of working life have become more diverse, but unions have become more monolithic, more distant and less able to respond to the needs of potential members. The old system of workplace reps, branch structures, annual conferences and factional bickering over places on national executive committees are the basis of the power for most of those inside union structures, and therefore it is almost no one’s interest to properly reform them, but they have locked unions into structures that are at best inappropriate and, more often, irrelevant to most workers in 21st Century Britain.

There has been plenty of union energy spent bickering over who can recruit where but there’s been too little recognition that unions now have to sell themselves to potential members and that their structures and strategies can’t be those that they used in the 1900s or the 1950s.

I believe that there is a future for a cooperative organisation that represents individual workers in times of crisis and that negotiates collectively on their behalf with employers and with government to promote and extend their rights. And I believe that unions can, and do, deliver real benefits for their members. The “union premium” – the amount by which union members’ wages outstrip non-union employees – is still almost 20%, worth, on average, more than £2 per hour, over £3500 per year for a full-time worker.

I sympathise with Len McCluskey and Unite’s desire to see a Labour Party that contains greater representation of people from working class backgrounds, but instead of trying to manipulate the Labour Party he’d be better off directing his energy on growing his union. Unite membership has fallen by 200,000 since 2008 and those actually paying into the union’s general fund has fallen faster, by 400,000, in that period.

If Unite (and the other unions) were growing, if they had adapted to the changing world of work, if they were attractive to young members and if they had developed services that were essential to the majority of British workers, then Unite wouldn’t have to be worrying about extending their influence within the Labour Party.

If unions were truly strong, if their own house was in order, the Labour Party would be dancing to their tune because of their proven ability to attract the people Labour needs to be elected as the next government.

The truth is that the bickering that has exploded into recriminations over the Falkirk selection is not a sign of renewed union strength but a symptom of their weakness. Changing the composition of the parliamentary Labour Party – however admirable a goal – will do nothing to address the long and critical decline of union membership and their growing irrelevance in the lives of most workers. Indeed there’s something depressingly ironic about Unite complaining about the parliamentary Labour Party’s failure to properly represent working people at precisely the time when the union movement as a whole is becoming less and less representative of the real working environment.

Once again union leaders are fighting the wrong battle. They’re looking to extend their influence at the top of politics while ignoring the fact that their own roots are rotting away, so that even if they win this fight (and I don’t think they can), they’re going to lose the war. And that’s bad news for British workers.

Sources

http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/6309/economics/trade-union-density-in-the-uk/

http://www.theworkfoundation.com/downloadpublication/report/68_68_british%20unions.pdf

http://www.tuc.org.uk/tuc/unions_main.cfm

http://hopisen.com/2013/len-fiddling-while-unite-burns/

http://www.certoffice.org/CertificationOfficer/files/f6/f696caa2-376a-48f8-bc75-d3d084e71514.pdf