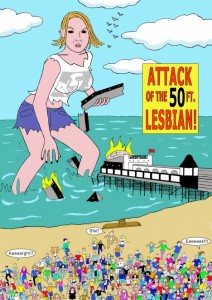

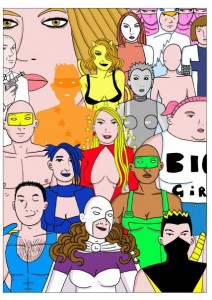

If Britain were going to have a superhero team made up of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual characters, then you’d expect them to live in Brighton. It’s the obvious choice. But that’s about the only predictable thing in Martin Eden’s indie comic series, Spandex. There’s an awful lot to like in these books, the twisty-turny storytelling, the simple, colourful and striking artwork, the memorable characters, and, for the most part, it all works extremely well. The fact that its lead characters are LGBT and that it deals smartly and sensitively with the issues raised by that fact is integral to the story, but it’s almost a bonus on top of what is (for want of a better word) straightforwardly engaging storytelling.

If Britain were going to have a superhero team made up of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual characters, then you’d expect them to live in Brighton. It’s the obvious choice. But that’s about the only predictable thing in Martin Eden’s indie comic series, Spandex. There’s an awful lot to like in these books, the twisty-turny storytelling, the simple, colourful and striking artwork, the memorable characters, and, for the most part, it all works extremely well. The fact that its lead characters are LGBT and that it deals smartly and sensitively with the issues raised by that fact is integral to the story, but it’s almost a bonus on top of what is (for want of a better word) straightforwardly engaging storytelling.

Eden originally conceived Spandex as taking the form of a single book containing five non-consecutive issues (1, 4, 8, 12 and 15) pulled from an imaginary on-going comic series, leaving the reader to fill in the continuity. As someone who grew up reading random issues of American Marvel comics I picked up (mostly on seaside holidays in Donegal), this struck me as a brilliant idea – this was precisely how I first encountered superhero comics.

However, that plan quickly fell by the wayside. Some of the episodic nature of the Spandex story (now up to issue six) still hints at Eden’s original vision, but what has emerged is (in form if not in content) a more traditional superhero story. Eden’s brightly coloured little A5 comics have been widely praised, earning him an Eagle nomination and a deal with Titan to collect the story (the first collection, Spandex: Fast and Hard containing the first three issues is released at the end of May).

The highlight of the book so far has been issue three – “If you were the last person on Earth” – which is a splendidly creepy science fiction tale let down only by a slightly Russell-T-Davies-ending. If the series has a weakness, it is issue five, which features Eden’s take on the obligatory “big event” crossover but there was too much introductory chat and too many characters and I had difficulty making sense of it all. Issue six, however, was a fine return to form and features a cliffhanging ending designed to drive any remaining readers of a conservative bent into a foaming fury.

The highlight of the book so far has been issue three – “If you were the last person on Earth” – which is a splendidly creepy science fiction tale let down only by a slightly Russell-T-Davies-ending. If the series has a weakness, it is issue five, which features Eden’s take on the obligatory “big event” crossover but there was too much introductory chat and too many characters and I had difficulty making sense of it all. Issue six, however, was a fine return to form and features a cliffhanging ending designed to drive any remaining readers of a conservative bent into a foaming fury.

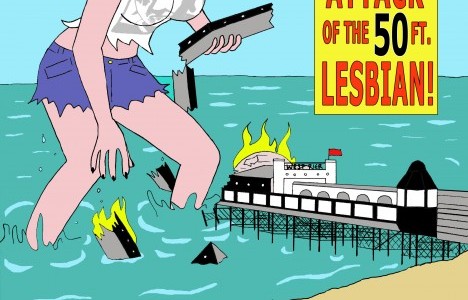

Spandex features a giant fifty foot lesbian, good jokes, genuine drama, sex, superhero punch-ups and moments of powerful affect – what more could you want from a comic? It’s a little crudely done in places, but it is tremendous entertainment and Eden’s open, emotionally honest writing style carries him over any bumps. You could wait for the Titan collection or you could go to http://spandexcomic.wordpress.com/ and get all six issues published to date, plus a collection of mini comics and a badge and stuff for just £15. I would if I were you. I’m looking forward to the next issue, which promises to wrap up the loose threads of the series so far.

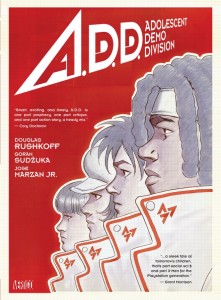

A far less successful comic is ADD: Adolescent Demo Division, written by Douglas Rushkoff with art by Goran Suzuka and Jose Marzan Jr (from Vertigo). I wasn’t keen on the artwork in this book, it lacked definition and detail and contributed to the sense that the story took place in a generically bland future. But the real villain in ADD isn’t the art, it isn’t even the tediously predictable evil corporate mastermind, it is Rushkoff’s unforgivably lazy writing.

A far less successful comic is ADD: Adolescent Demo Division, written by Douglas Rushkoff with art by Goran Suzuka and Jose Marzan Jr (from Vertigo). I wasn’t keen on the artwork in this book, it lacked definition and detail and contributed to the sense that the story took place in a generically bland future. But the real villain in ADD isn’t the art, it isn’t even the tediously predictable evil corporate mastermind, it is Rushkoff’s unforgivably lazy writing.

To say that the book’s plot is overly familiar would be an understatement of a very high order. That Rushkoff could then make such a familiar stew so instantly forgettable, and I have the book open in front of me and I still can’t recall any specifics of the plot, takes a special lack of talent. The story, what I can recall of it, features kids who are apparently being bred to play video games but are actually part of some industrial/military conspiracy. There’s a big-cheese corporate villain, who is moronically sketched out and whose big idea seems to be to sell kids who play video games giant life-size robots of other, genetically altered, kids who are infinitely better than them at video games – thereby ensuring that they are constantly humiliated by the huge automaton in their bedroom. And then there’s the shallow characterisation of the core characters, the cool older kid who is obviously doomed, the insightful one whose a bit like Neo from The Matrix, the bully, the bully’s chubby muscle (there must be a shop where bullies go to get big, silent, fat kids to do their dirty work) and a girl who doesn’t get to do much – no tedious stereotype or overworked cliché is given a miss.

The story meanders around a bit but doesn’t spring any surprises (the scientist is what?) and then it all ends with a plop as the kids all upload themselves to something and apparently set themselves free – though what’s to stop the evil businessmen from just turning off their servers and wipe them out isn’t explained, but then neither is anything else, so best to just let it go.

What makes ADD all the more annoying is the po-faced presentation, with blurb from (better) writers that lead you to believe that this book has something interesting to say about the media society in which we live. It doesn’t, it’s a juvenile book in the worst possible sense.

If you are looking for a comic that says something interesting about our modern, media-drenched, society and does it in a genuinely provocative and thrilling way, your time would be far more rewardingly spent picking up The Nightly News, by Jonathan Hickman (first released in 2007 but now re-released in hardback from Image).

If you are looking for a comic that says something interesting about our modern, media-drenched, society and does it in a genuinely provocative and thrilling way, your time would be far more rewardingly spent picking up The Nightly News, by Jonathan Hickman (first released in 2007 but now re-released in hardback from Image).

There are no compromises in this book. It revolves around the actions of a group of vigilantes who set out to strike back at America’s corrupt and manipulative press in the most brutal manner – shooting and blowing up journalists. This is an angry, dense book – it eschews, mostly, the traditional comic style of panels and splash pages – and instead mixes infographics and drawing and tiny text and endnotes and asides and running jokes and quotes into a complicated story of betrayal, lies and murder.

Hickman has become better known, since this book’s original release, for his work on Marvel superhero books, particularly his take on The Fantastic Four, but there are no heroics (super or otherwise) here. There are no cute characters or accessible routes into this story, it grabs you and shakes you and demands that you think. In places it is almost all too much – tiny text, graphical overload, unforgiving storytelling – means that you have to put considerable effort into reading this book, but it certainly repays your hard work.

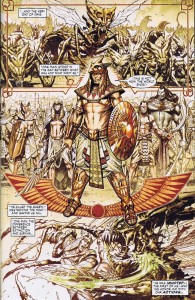

To coincide with the hardback reissue of The Nightly News, Image have also rereleased a number of other early Hickman stories. The Red Wing is a time travel/paradox story which reads a bit like one of those 2000AD short Future Shocks, but spread over rather too many pages. Nick Pitarra’s artwork is very striking but, although there is a hint of something interesting in Hickman’s writing about the conflict between generations, it is never fully explored and is rather undermined by the too predictable twist ending. Red Mass for Mars is a superhero tale which, although it features all the familiar spandex archetypes (the superman, the crime fighter, the inventor, the mage) does manage to do something interesting with the idea. In the far future Earth faces invasion from an apparently unstoppable foe and the remaining few super-powered individuals must find a way to put aside old differences to save the planet. Within this familiar outline, Hickman manages to play with our expectations and to deliver a few moments I found genuinely shocking. Once again he’s supported by some fine artwork (this time from Ryan Bodenheim) and if Red Mass for Mars isn’t quite a great book, it is certainly a very good one.

To coincide with the hardback reissue of The Nightly News, Image have also rereleased a number of other early Hickman stories. The Red Wing is a time travel/paradox story which reads a bit like one of those 2000AD short Future Shocks, but spread over rather too many pages. Nick Pitarra’s artwork is very striking but, although there is a hint of something interesting in Hickman’s writing about the conflict between generations, it is never fully explored and is rather undermined by the too predictable twist ending. Red Mass for Mars is a superhero tale which, although it features all the familiar spandex archetypes (the superman, the crime fighter, the inventor, the mage) does manage to do something interesting with the idea. In the far future Earth faces invasion from an apparently unstoppable foe and the remaining few super-powered individuals must find a way to put aside old differences to save the planet. Within this familiar outline, Hickman manages to play with our expectations and to deliver a few moments I found genuinely shocking. Once again he’s supported by some fine artwork (this time from Ryan Bodenheim) and if Red Mass for Mars isn’t quite a great book, it is certainly a very good one.

I also read some of Hickman’s work for Marvel this month, SHIELD: Architects of Forever, but I don’t feel I can review it properly because although, in theory, it is a complete mini-series collected in a graphic novel it is actually half a story and I want to reserve judgement until I’ve seen how things work themselves out in the forthcoming second series. As it stands, however, SHIELD is a fantastically complicated thing featuring a large cast of historical figures, including, Galileo, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Newton, Nostradamus and Tesla and minor characters from Marvel’s universe (the fathers of Reed Richards and Tony Stark) with time travel and galactic threats and things living in the sun and betrayal. These characters are caught up in the work of Shield, an ancient organisation committed to defending the planet from the threat of anhilation and whose rallying cry is: “This is not how the world ends.” The obvious suggestion is that this will all, somehow, tie in to Marvel continuity and the secret government ageny, SHIELD, sometimes led by Nick Fury, but how that might work and whether it will be even remotely relevant isn’t clear. And I’m not sure it matters, because this story seems to be working perfectly well on its own terms, without the need for retconning or obeisance to decades of existing continuity. I still can’t tell whether it’s going to be brilliant or collapse into total bunkum, but this is a book worth picking up just for the fabulous artwork by Dustin Weaver, whose detailed pages could occupy your eyes for hours. I hadn’t come across his art before, but I’ll be looking out for more.

I also read some of Hickman’s work for Marvel this month, SHIELD: Architects of Forever, but I don’t feel I can review it properly because although, in theory, it is a complete mini-series collected in a graphic novel it is actually half a story and I want to reserve judgement until I’ve seen how things work themselves out in the forthcoming second series. As it stands, however, SHIELD is a fantastically complicated thing featuring a large cast of historical figures, including, Galileo, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Newton, Nostradamus and Tesla and minor characters from Marvel’s universe (the fathers of Reed Richards and Tony Stark) with time travel and galactic threats and things living in the sun and betrayal. These characters are caught up in the work of Shield, an ancient organisation committed to defending the planet from the threat of anhilation and whose rallying cry is: “This is not how the world ends.” The obvious suggestion is that this will all, somehow, tie in to Marvel continuity and the secret government ageny, SHIELD, sometimes led by Nick Fury, but how that might work and whether it will be even remotely relevant isn’t clear. And I’m not sure it matters, because this story seems to be working perfectly well on its own terms, without the need for retconning or obeisance to decades of existing continuity. I still can’t tell whether it’s going to be brilliant or collapse into total bunkum, but this is a book worth picking up just for the fabulous artwork by Dustin Weaver, whose detailed pages could occupy your eyes for hours. I hadn’t come across his art before, but I’ll be looking out for more.

Lastly for now and, sadly, by every means least is Ziggy Marley’s Marijaunaman by Jim Mahfood and Joe Casey, which is a dreadfully bad comic book from Image. I’ve liked both Mahfood’s and Casey’s work on other projects, but Marijuanaman is every bit as stupid and crass as the title suggests. For me the major social ill caused by marijuana is the danger of being cornered by some stoned loon and lectured to death about the wonders dope is and how evil “the man” is – Marijuanaman captures that horror with an almost uncanny precision. You can, I have been told, make almost anything out of hemp. Anything except, I think, a conversation that does not leave me wishing to dash my brains out against the nearest brick wall.

Lastly for now and, sadly, by every means least is Ziggy Marley’s Marijaunaman by Jim Mahfood and Joe Casey, which is a dreadfully bad comic book from Image. I’ve liked both Mahfood’s and Casey’s work on other projects, but Marijuanaman is every bit as stupid and crass as the title suggests. For me the major social ill caused by marijuana is the danger of being cornered by some stoned loon and lectured to death about the wonders dope is and how evil “the man” is – Marijuanaman captures that horror with an almost uncanny precision. You can, I have been told, make almost anything out of hemp. Anything except, I think, a conversation that does not leave me wishing to dash my brains out against the nearest brick wall.

Marijuanaman features an alien whose mystical powers are unleashed in the presence of one unique, Earthly herb. And no, it’s not oregano. This alien lives on a commune, the last refuge of Rastafarian-ish hemp growers, who are fighting back against evil big business (a recurring theme this month). In this case the foe is a giant pharmaceutical company, Pharma-Con, who wants to destroy natural highs so they can profit by getting the innocent people of Earth addicted to its nasty chemical drug, Ganjarex. There’s an ineptly conceived mercenary supervillain, Cash Money, and some guff about higher consciousness and the evils of capitalism and not a lot of sense in this slim, overpriced hard back.

There are lots of important points to be made about the pointlessness of the on-going “war on drugs”, the ultimate futility of prohibition and the double-standards that apply to some addictive substances and not to others in our society. Marijuanaman doesn’t bother with any of those and the few coherent points it does make are crude and often irrelevant.[i]

Some people might object that this comic presents the positive case for cannabis without any hint of the possible damage it can do (all drugs have side-effects).

Such people should not concern themselves.

Indeed, I believe that, if picked up by curious teenagers seeking information about recreational drug use, Marijuanaman could well be a more effective aversion therapy than any government-backed scheme. So tedious is the cod-philosophising and so extravagantly stupid is the storytelling that there is a genuine possibility that, if someone (Michael Gove, for instance) decided to widely distributed Marijuanaman to (say) every school in the country and make it a compulsory part of the curriculum, this book might, on its own, make weed history.

There are people who claim that drug use offers creative insight and that new artistic horizons are revealed for those willing to open their minds. Marijuanaman suggests that, at the very least, this is not a universal truth.

[i] I honestly don’t think that one of the reasons dope is illegal in so many countries has anything to do with the threat hemp presents to existing textile industries.