One of the things that I’ve got back into thanks to the purchase of a tablet is regularly reading comics bought via Comixology. Having got the taste electronically, I’ve also started to pick up a number collected editions and graphic novels. So I thought I might start off putting together a monthly review of the stuff I’ve read. We’ll see how that works out, but here’s the first attempt, looking at a new Daredevil, Mystery Men and Goliath.

Daredevil has usually operated somewhere on the edge of the Marvel universe, never the most popular book but well-established enough to keep the character in regular publication for almost 50 years. I think even Stan Lee would confess that the character wasn’t the strongest creation of the wildly fertile period he enjoyed in the early 1960s. Daredevil was always in danger of sliding too close to becoming a cheap Spider-Man clone, the supporting characters in Matt Murdock’s life could be one-dimensional and his alter-ego’s rogues gallery could often look like cast-offs. But being on the edge of things has meant that, sometimes, it has been a place for experimentation.

Daredevil has usually operated somewhere on the edge of the Marvel universe, never the most popular book but well-established enough to keep the character in regular publication for almost 50 years. I think even Stan Lee would confess that the character wasn’t the strongest creation of the wildly fertile period he enjoyed in the early 1960s. Daredevil was always in danger of sliding too close to becoming a cheap Spider-Man clone, the supporting characters in Matt Murdock’s life could be one-dimensional and his alter-ego’s rogues gallery could often look like cast-offs. But being on the edge of things has meant that, sometimes, it has been a place for experimentation.

In the late 60s, while the rest of Marvel was dominated by the squared-off styles of Kirby and Romita, Daredevil was being drawn by the darker and more fluid pen of Gene Colan[i]. Colan’s eighty issues ran through until 1973. Later that decade Frank Miller would begin to take the character in a new, famously darker, direction that would change the whole superhero genre. Daredevil was the place that Miller cut his teeth as a storyteller and that early 1980s run on Daredevil remains Miller’s best work as a writer of comic books[ii]. From 1987, Ann Nocenti enjoyed a four-and-a-half year run as writer, frequently with the beautiful art of John Romita Jnr, and turned The Man Without Fear into a crusading, liberal do-gooder. This remains one of my favourite periods in the book’s history. The 1990s were a bad decade for Marvel, the company filed for bankruptcy in 1996 and the quality of comics was hardly higher than the quality of its accounting. From this disastrous period Daredevil would be the place where the seeds of the company’s revival would be sown. Marvel gave control of a handful of characters, the Marvel Knights, to Joe Quesada who first brought Kevin Smith then Dave Mack and, in his first Marvel role, Brian Michael Bendis to the pages of Daredevil. The result was consistently excellent comic books and Quesada, Bendis and others would effectively rebuild Marvel Comics. The good run continued into the 2000s with Brubaker and Lark’s noir-tinted era.

But even in the good times must contain some bitterness. The best that can be said for Andy Diggle’s recent period as Daredevil writer (and the, frankly misconceived, Shadowland storyline – in which Daredevil was possessed by a demon and lead a ninja army to control his New York stomping ground, Hell’s Kitchen) is that it has not marked a high-point in the history of the book.

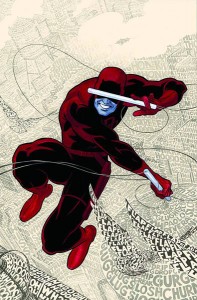

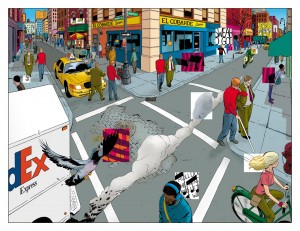

Which makes the relaunched Daredevil (it’s now up to Volume 3), under the authorship of Mark Waid and with Paulo Rivera’s artwork, a bit of a treat. The first six issues are now available in a collected edition and it’s a joyful thing. Waid has said he wants to change the balance between adventure and depression in Matt Murdock’s life, and that’s apparent from the start. While it is clear that Waid isn’t going to let Matt Murdock to just walk away from his past, there are some wonderful passages in the new comic that just have Matt and his old friend Foggy bantering – issue one features a nine page short story of them walking through the streets of New York’s Hell Kitchen, just chatting, and it’s brilliantly done. Rivera’s graphic representation of Matt Murdock’s “sonar” powers is one of the most distinctive and striking that I’ve ever seen.

Which makes the relaunched Daredevil (it’s now up to Volume 3), under the authorship of Mark Waid and with Paulo Rivera’s artwork, a bit of a treat. The first six issues are now available in a collected edition and it’s a joyful thing. Waid has said he wants to change the balance between adventure and depression in Matt Murdock’s life, and that’s apparent from the start. While it is clear that Waid isn’t going to let Matt Murdock to just walk away from his past, there are some wonderful passages in the new comic that just have Matt and his old friend Foggy bantering – issue one features a nine page short story of them walking through the streets of New York’s Hell Kitchen, just chatting, and it’s brilliantly done. Rivera’s graphic representation of Matt Murdock’s “sonar” powers is one of the most distinctive and striking that I’ve ever seen.

Waid is also smart, I think, by returning Matt Murdock, and the focus of the book, to the courtroom. There’s fun to be had playing off the fact that Murdock’s identity has been one of the most frequently revealed “secrets” in comic book history but it also forces Matt to find alternative ways to help people. Of course, this being a superhero title, battles between Daredevil and lycra-clad villains (and occasionally heroes) are unavoidable, but Waid handles these lightly. Klaw, a Marvel villain who must be punch-drunk after years of beatings at the hands of various heroes, gets a clever reworking and a new, deliberately crap, villain (The Bruiser) is introduced and dismissed effectively. I particularly like this character because, like a racing car driver, his costume carries sponsors logos. But unlike, say, Jenson Button, The Bruiser carries adverts for Marvel’s evil super corporations like AIM and the Serpent Society, which made me laugh.

The new Daredevil is a pleasure, and I’m looking forward to reading more.

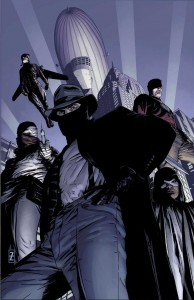

Also published by Marvel is Mystery Men by David Liss and Partrick Zircher. This is very nearly a really good comic. Liss writes smoothly and smartly and Zircher’s artwork deftly captures the 1930’s aesthetic of the comic’s setting. Mystery Men is an attempt to retrofit the Marvel Universe into the depression era. Liss, probably better known as a novelist of books like The Conspiracy Papers, creates a new set of heroes that feel authentically pulpy. There’s a privileged cat burglar, a mysterious night-stalker, the possessor of a powerful mythical object, a mad-scientist and a jet powered science hero. None of this is novel, but what is potentially interesting about Mystery Men is the use Liss makes of his Depression-era setting and the political agenda it allows him to pursue.

Also published by Marvel is Mystery Men by David Liss and Partrick Zircher. This is very nearly a really good comic. Liss writes smoothly and smartly and Zircher’s artwork deftly captures the 1930’s aesthetic of the comic’s setting. Mystery Men is an attempt to retrofit the Marvel Universe into the depression era. Liss, probably better known as a novelist of books like The Conspiracy Papers, creates a new set of heroes that feel authentically pulpy. There’s a privileged cat burglar, a mysterious night-stalker, the possessor of a powerful mythical object, a mad-scientist and a jet powered science hero. None of this is novel, but what is potentially interesting about Mystery Men is the use Liss makes of his Depression-era setting and the political agenda it allows him to pursue.

The Operative, the thief, is a Robin Hood character who targets the ultra-wealthy. The night-stalker, The Revenant, is a black man in a segregated era who explicitly addresses issues of racial discrimination. The mad scientist, The Surgeon, is a doctor who refuses to be cowed by local strike-breakers and continues to treat those they have beaten. The forces of reaction take their revenge by almost burning the doctor to death. The thread that ties these three together (and draws in two others – Achilles, an archaeologist who is tasked to return a mystical amulet from Troy, and Aviatrix the Rocketeerish sister of The Operative’s murdered girlfriend) is the scheming of the General and his committee of New York’s wealthiest, and least principled, elite. This group is manipulating America, extending the suffering of the Depression, to advance their own agenda and increase their control. They direct a corrupt police force, who connive with their cruelty and act as a brutal tool of oppression.

Mystery Men has an exceptionally interesting set up, but it doesn’t deliver. Liss dilutes the potential of his premise by introducing an evil she-demon, Nox, who is secretly responsible for directing the work of the General and his committee. It seemed to me that there was more than enough evil in his capitalist cabal and all the mystical villainess achieves is to undermine the points Liss seems to be trying to make. Liss sets up characters with quite specific motivations, to have his characters fail to follow the path he has set them on seems like a loss of nerve on behalf of the author or his editors. It is interesting, however, to see (even if imperfectly) radical questions about the relationship between the wealthy elite and the masses making it into publications from a publisher like (Disney-owned) Marvel and to see how the rhetoric of the “Occupy” movement is beginning to percolate into popular media.

Mystery Men has an exceptionally interesting set up, but it doesn’t deliver. Liss dilutes the potential of his premise by introducing an evil she-demon, Nox, who is secretly responsible for directing the work of the General and his committee. It seemed to me that there was more than enough evil in his capitalist cabal and all the mystical villainess achieves is to undermine the points Liss seems to be trying to make. Liss sets up characters with quite specific motivations, to have his characters fail to follow the path he has set them on seems like a loss of nerve on behalf of the author or his editors. It is interesting, however, to see (even if imperfectly) radical questions about the relationship between the wealthy elite and the masses making it into publications from a publisher like (Disney-owned) Marvel and to see how the rhetoric of the “Occupy” movement is beginning to percolate into popular media.

Ultimately, while Mystery Men is a pretty book to look at and contains some interesting ideas, it fails to live up to its potential.

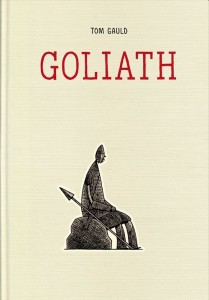

There are no superheroes in Tom Gauld’s brilliant Goliath (Drawn & Quarterly). I’ve been a big fan of Guald’s work on the letter page of The Guardian’s Saturday Review for a long time and have eagerly anticipated this publication.

There are no superheroes in Tom Gauld’s brilliant Goliath (Drawn & Quarterly). I’ve been a big fan of Guald’s work on the letter page of The Guardian’s Saturday Review for a long time and have eagerly anticipated this publication.

It was worth the wait.

Gauld takes the biblical story and turns it on its head, telling it from Goliath’s perspective. Even better, though, is the fact that this Goliath is not the ravening monster of Jewish mythology. This Goliath is huge but he’s no great warrior, as he points out he’s “the fifth worst swordsman in my platoon… I do paperwork! I’m a very good administrator.”

Despite his protests, Goliath is recruited by an ambitious general determned to advance his prospects by delivering a cheap Philistine victory over the Israelites. He is given an impressive looking suit of bronze armour (which, unfortunately, immediately begins to fall apart) and with an enormous sheild, a spear and a tiny shieldbearer he is sent out to demand the enemy’s champion meet him in single combat. The general reckons that Goliath’s size will mean that no one will dare face him and the Philistines will win by default.

Goliath is a very funny book, but it is bittersweet. Goliath is a gentle soul forced into a role for which he is utterly unsuited. It is a story told through wonderful pauses, Goliath faints when he is shown the declaration he must roar at the Israelites, the days drag by as the Israelites refuse Goliath’s challenge, there’s an escaped fighting bear and a confused shepherd.

Goliath is a very funny book, but it is bittersweet. Goliath is a gentle soul forced into a role for which he is utterly unsuited. It is a story told through wonderful pauses, Goliath faints when he is shown the declaration he must roar at the Israelites, the days drag by as the Israelites refuse Goliath’s challenge, there’s an escaped fighting bear and a confused shepherd.

And then, at last, David arrives.

But the future king’s inevitable victory is no great triumph. David’s boasting and brutality and his silly bloody pebble are cruel and Goliath’s death is pointless and unfair.

Gauld’s artwork seems simple, spare even, but it is wonderfully evocative and perfectly suits his understated but affecting writing. Guald uses humour with great intelligence, strengthening rather than undermining the emotional impact of his story. There are good jokes throughout the book but they are never at the expense of our growing attachment to his protagonist and the final pages pack a surprising emotional impact.

If you’re going to buy one graphic novel this month, make it Goliath.

[i] As a kid, reading Daredevil, I didn’t get Colan’s artwork – often the lines and shading were so dark in those Marvel UK black-and-white reprints that they were almost unreadable. It’s really only when you see those strips in colour that they really make sense.

[ii] Too much of his later work has been marred by the fact that he rapidly came to believe his own hype and, of course, his increasingly potty rightwing extremism.