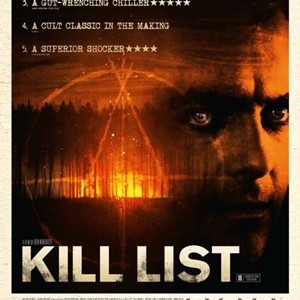

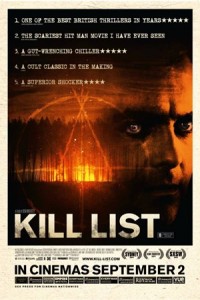

Superficially, the opening passages of Kill List could be taken as the introduction to another Brit-made gangster movie. The central characters, Jay and Gal are guns for hire – mercenaries who do very dirty work. They’ve got a history together, including a visit to Kiev eight months before that, it is suggested, went very wrong. Whatever happened in Kiev, Jay emerged damaged and hasn’t worked since. Money is running out, tensions are growing between Jay and Shel, his wife, and Gal is pestering him to take a new job.

Superficially, the opening passages of Kill List could be taken as the introduction to another Brit-made gangster movie. The central characters, Jay and Gal are guns for hire – mercenaries who do very dirty work. They’ve got a history together, including a visit to Kiev eight months before that, it is suggested, went very wrong. Whatever happened in Kiev, Jay emerged damaged and hasn’t worked since. Money is running out, tensions are growing between Jay and Shel, his wife, and Gal is pestering him to take a new job.

The opening twenty minutes could be the set up for any other “just-one-more-job” crime movie. But no one who sits through Kill List’s first act could be in any doubt that there’s something much, much stranger going on here. The opening sequences are domestic, the relationships between Jay, Gal and Shel (Neil Maskell, Michael Smiley and MyAnna Buring – all excellent) are wholly convincing but the mood is brooding and almost unbearably tense – underscored by intimate camera work and a sparse, menacing score.

A dinner party brings an explosive row and Jay is forced to accept that he has to go back to work. A meeting with a client brings a kill list of three targets: the priest, the librarian and the MP, and enough cash to fix the Jacuzzi.

And then things start to get very violent and increasingly strange.

If you read the reviews of Kill List on something like IMDB or Amazon you’ll find plenty of rave reviews but you’ll also find those balanced by a raft of “one star” complaints about unsympathetic characters, brutal violence and, most often, an infuriating ending.

The negative reviews are, in a sense, spot on. But they also completely miss the point.

The idea that every successful story needs a protagonist who is sympathetic is one of those bizarre mantras that escaped from books that purport to teach people how to write. Like rhododendrons, which probably once seemed exotic and pretty, this notion has escaped from carefully cultivated gardens and invaded every open patch of land, throttling the perfectly good native fauna and blighting the landscape. Mostly complaints about sympathetic characters are based on the misunderstanding that sympathetic, in this sense, is a synonym for likeable. It is true that none of the characters in Kill List are likeable. And it is also easier to write a story that engages a reader or viewer when the protagonists are likeable – if we’re going to spend time with people, we’re usually happier if it is someone we want to be with. But successful stories don’t rely on us liking the protagonist, they simply require us to have an insight into why a character chooses a particular path and how they reach their decisions. The sympathy we require is understanding, not admiration or even affinity for a character’s personality.

The main thing that seemed to annoy people about Kill List, however, is the ending.

Again, it seems to me, that many of the reactions are based on a misunderstanding. Some reviewers seemed to believe that this is a film with a twist ending. The last moments of Kill List are certainly supposed to shock, but I don’t think they are supposed to surprise. There is no attempt, during Kill List, to misdirect the viewer. On the contrary, the film is almost relentlessly single-minded in foreshadowing the disaster that is inevitable from the opening minutes. We are (literally – if you pay attention) shown what is to come. There is no twist.

One thing that can’t be denied about the end of Kill List, however, is that it does not offer any neatly-packaged answers. There’s no drawn out exposition to clarify why Jay’s victims all said “thank you” as he killed them. There’s no villain’s monologue that explains the manipulations that had gone to bring us to this denouement. There is no moment of revelation in which we get to see Jay’s “condition” laid out before us. It is clear from their reactions that some of Kill List’s one star reviewers found the lack of explanations in the ending intolerable.

The successful resolution of a narrative does not, solely, depend on the completeness of its explication of the elements of plot and motivation. Stories and writers can, and should, make demands of their audiences. Sometimes the stories that leave us with nagging doubts and the unanswered questions are the ones that live longest in our memories.

Kill List will frustrate those who demand easy answers. At times its brutality will cause even the most hardened horror viewers to wince. There are no comforting lessons to learn and nothing to provide heart-warming consolation on dark winter nights.

But Kill List has plenty to offer those looking for a smarter horror movie and it’s a very promising debut from British writer/director Ben Wheatley and his screenwriting partner Amy Jump.