There is, when you think about it, a surprisingly long list of very good films about boxing. Consider just the biopics: Raging Bull (the story of Jake LaMotta); Somebody Up There Likes Me (Rocky Marciano); The Hurricane (Rubin Carter); Gentleman Jim (Jim Corbett); Cinderella Man (James J Braddock); and The Fighter (Micky Ward). On top of that can be added purely fictional stories like The Harder They Fall (Bogart’s last film), On the Waterfront, Rocky, Requiem for a Heavyweight, Million Dollar Baby, The Set Up and all the way back to the magnificent Wallace Beery in The Champ. And then there’s one of the finest documentaries about sport ever made: When We Were Kings.

There is, when you think about it, a surprisingly long list of very good films about boxing. Consider just the biopics: Raging Bull (the story of Jake LaMotta); Somebody Up There Likes Me (Rocky Marciano); The Hurricane (Rubin Carter); Gentleman Jim (Jim Corbett); Cinderella Man (James J Braddock); and The Fighter (Micky Ward). On top of that can be added purely fictional stories like The Harder They Fall (Bogart’s last film), On the Waterfront, Rocky, Requiem for a Heavyweight, Million Dollar Baby, The Set Up and all the way back to the magnificent Wallace Beery in The Champ. And then there’s one of the finest documentaries about sport ever made: When We Were Kings.

The most affecting boxing movies are often stories of redemption, of strong men (and very occasionally, women) finding a space between the ropes where they can transcend their frailties. Despite the tough guys and the brutal fighting, boxing movies are most often tales of human weakness.

It’s a fact that makes Real Steel’s decision to remove the human from the ring either brave or stupid.

Real Steel is a boxing movie set in a near future in which robots have replaced human fighters (though the rest of the world appears unchanged). It has excellent special effects and, for the most part, it has nicely choreographed fights. There’s none of the hyper-kinetic lunacy of Michael Bay’s Transformers and the film is better for it. The restraint imposed by the (approximate) Marquess of Queensbury rules, allows the film to show off its cleverly designed (though physically improbable) machine creations to good effect.

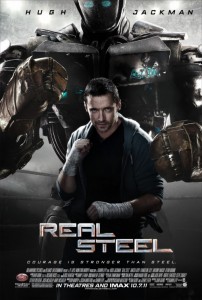

Charlie Kenton (Hugh Jackman) is a former boxer who never quite made it in the big time and who, when human fighters are replaced by machines, doesn’t quite make it as the manager of fighting robots. Charlie suddenly finds himself lumbered with a son, Max (Dakota Goyo), when his ex-girlfriend dies and he takes her rich brother-in-law’s money to look after the boy while they go on holiday. Max finds an obsolete training robot and father and son embark on one of those sickly Hollywood journeys of discovery in which Max gets to love, admire and respect his father and Charlie gets to learn a lesson about responsibility, get the girl and box his way to glory.

No one goes into a boxing movie expecting originality, there are hoops we need these films to jump through and, sensibly, Real Steel follows a well-worn path. It lifts cues from Rocky, The Champ and Cinderella Man amongst others and it twists them together into a structure that works reasonably well. But, despite some nicely unsentimental banter between Charlie and Max, the characters are just too sketchily drawn to make them feel real. The emotional arc of their relationship is too predictably treacle-laden and lacks any semblance of authenticity. These are characters that come pre-sliced, vacuum-packed and ready-to-eat – they are bland, familiar and utterly disposable.

And, it turns out, despite the spectacle the robots allow, taking the human out of the ring was a serious mistake.

There are moments in which Real Steel is like watching a very high tech version of Rock’em Sock’em Robots and, for all the flashy graphics, it never manages to become any more emotionally engaging than waching a red and a blue plastic robot attempt to batter each other while two kids hammer endlessly on a single button. Atom, the little robot who Max rescues from a dump and turns into a world champion, is a cleverly done and the designers have worked hard to make it appealing without making it sickeningly cute. We want to like Atom. But, as the characters keep reminding us, it is just a machine.

In a boxing movie redemption comes through the display of physical courage. Whatever the failures of their character, we see the boxer at their best in the ring where they suffer and endure and, sometimes, come good. The square ring is a confessional, a place of penitence, where sins are washed away.

But in Real Steel Charlie doesn’t suffer. Charlie doesn’t display courage. Charlie doesn’t earn his redemption. Atom gets battered by a series of increasingly enormous robots. Charlie and Max shout a bit. Everyone gets teary-eyed.

So, when Charlie gets everything he’s always wanted – glory, riches, girl – it’s because of another character’s suffering and that denies the heart of a boxing story. It hollows out the film’s emotional and ethical core and it fundamentally weakens Real Steel. Despite the fact that there are things to like about this film, when the end came and the underdogs triumph, I found I didn’t really care. And that, surely, is a knock-out blow.